If 2012 saw a lot of buzz in India about Jugaad thanks to the Radjou/Prabhu/Ahuja bestseller, I am really hoping that 2013 will restore the balance towards systematic innovation. Indian companies need systematic innovation more than they realize because their challenges are different from the ones that multinationals face.

Why are Indian Companies afraid of Systematic Innovation?

Among Indian entrepreneurs, even in large business houses, the fear of systematic innovation is that it will hamper them from being opportunistic, and prevent them from being agile and quick. They point to multinationals who lose out to nimble local competitors, such as a Nokia being eclipsed by a Samsung.

But I wonder whether it’s fair to attribute the travails of large multinationals to their systematic innovation processes. It’s well known that as companies become large, they tend to become more focused on predictability and efficiency than on disruption or innovation. They tend to get more obsessed with “what analysts will say” than what is right for their company. And, they tend to get more bogged down by the “dominant logic” of what made them successful in the past rather than what will help them succeed in the future.

There are several recent examples that corroborate these observations: Nokia had developed touch screen phones well before the Apple iPad made them the “next big thing.” Kodak, which recently filed for bankruptcy, was one of the pioneers of digital photography technology but allowed other companies to take over that space. These examples suggest that risk aversion and “prediction disability” (and not systematic innovation processes!) prevented these otherwise iconic companies from capitalizing on their innovations.

Once you go even slightly higher up the technology ladder, systematic innovation becomes inevitable for success. Consider any of the companies that I wrote about in the last year – 3M, possibly the most innovative company of all times; IBM, still a powerhouse of innovation with more than 6,500 US patents granted in calendar 2012; or Cisco, one of the first multinationals to create a world class product end-to-end from India. Or Indian companies like Titan, whose disciplined efforts to build innovation capabilities ground up from the shopfloor have resulted in huge savings of time and precious metals; and Eureka Forbes, whose efforts to commercialize the best technologies in water purification have resulted in Amrit, a process that tackles even bio-organisms. None of these companies could have achieved even a fraction of these results without following systematic approaches to innovation.

I believe that systematic innovation has got a bad press because it has been confused with the dynamics of decision-making in large organizations. A clearer understanding of what systematic innovation is, and what it’s not, should establish why embracing systematic innovation will help rather than hinder innovation.

What Systematic Innovation Is…

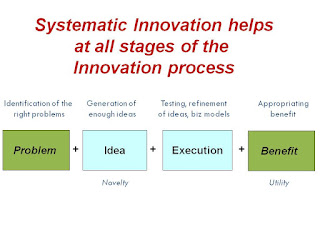

An approach to innovation that enhances the number of ideas being generated and considered so as to improve the odds of innovation success. [Research shows that it often takes more than 300 ideas to result in one successful product.]

Greater, structured connections with users/customers and other stakeholders to help align innovation with market needs. [Remember my article on why the Tata Ace was much more successful than the Tata Nano?]

A focus on experimentation and testing to check out assumptions, refine and reinforce ideas, and make innovations more robust and scalable.[Remember the motto of IDEO, the leading design firm: “Enlightened trial & error succeeds over the planning of the lone genius.” With enhanced user aspirations, the “integrity” of any innovation as reflected in the experience of the user is essential to innovation success. Innovation is much more than ideation, it is about execution to provide sustained benefits to users/customers. When a company like Apple puts an inadequately tested map utility on its latest iPhone, or Tata Motors fails to address safety issues adequately in pre-launch testing as appeared to happen with the Nano, an otherwise high potential innovation loses its sheen. As does an e-commerce site when it doesn’t support all browsers!]

Leveraging the power of many rather than depending on the intelligence of the few. [Open source software development has demonstrated the power of harnessing the wider community in product development. Open source methods are now being extended to challenging domains such as drug development. And companies like P&G and Eureka Forbes have shown that open innovation can be a source of unusual ideas.]

And What its not…

Systematic innovation does not necessarily mean huge investments in R&D. In fact, studies have repeatedly shown that the most effective innovators are not those who spend the most on R&D. As consulting firm Booz showed in their 2006 innovation report, effective innovators excel at processes like ideation, project selection, and commercialization, all part of the systematic innovation process!

Systematic innovation does not mean doing basic research or trying to pioneer new technologies. Firms like Titan Industries have shown that systematic innovation works very effectively even with improvements in traditional jewellery manufacturing processes.

Systematic innovation does not necessarily mean long drawn innovation cycles. Effective innovators find low-cost and quick ways of experimenting that help them test ideas and assumptions rapidly. They try to do what A.G. Lafley calls “Doing the last experiment first” – test the assumptions that will have a critical bearing on innovation success or failure early so as to avoid going down tracks that lead to nowhere.

2013: The Year of Systematic Innovation?

Ind ian companies need to embrace systematic innovation so as to capitalize on their innate abilities of intuition and market sensing. Vinay Dabholkar and I hope that 2013 will be the year for systematic innovation in India. May systematic innovation go viral! Our own contribution towards this will be released soon – watch this space for more details!

ian companies need to embrace systematic innovation so as to capitalize on their innate abilities of intuition and market sensing. Vinay Dabholkar and I hope that 2013 will be the year for systematic innovation in India. May systematic innovation go viral! Our own contribution towards this will be released soon – watch this space for more details!