Two copies of Walter Isaacson’s biography of Steve Jobs have been on my bookshelf for close to two years now, but the size of the book deterred me from starting to read it. I didn’t think I was ready to read 570 pages about the enfant terrible, particularly after I heard that the book had several instances of his petulant and downright bad behavior. So, I must thank my colleague and friend Sourav Mukherji for giving me the impetus to start reading it. And, I was not disappointed. In fact, I spent two whole days immersed in the book, literally gobbling every word in print (yes, I still read books the old-fashioned way!).

As I was reading, one question kept popping up in my mind – could we have a Steve Jobs from India? The immediate trigger came from a recent interview in Mint with legendary tech investor, Vinod Khosla, in which he said that the environment for entrepreneurship in India is improving, and we could see a Facebook or Google in the years ahead. I have asked similar questions earlier, most prominently in one of my columns in Outlook Business.

What made Steve Jobs “Steve Jobs”?

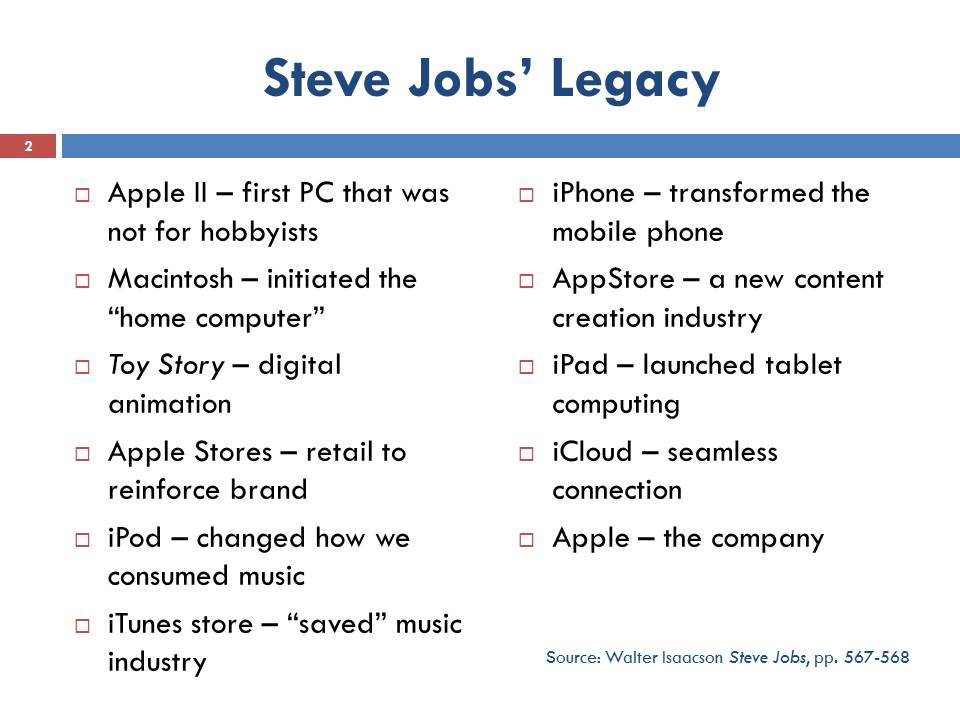

I guess I don’t need to list Steve Jobs’ accomplishments here (Isaacson lists eleven instances where Steve’s products transformed industries! – see below).

So, let’s jump forward and take a look at the man himself.

So, let’s jump forward and take a look at the man himself.

Steve had some distinctive characteristics: A keen sense of aesthetics; an eye for detail; an intuitive understanding of what makes for an outstanding user experience; a belief in simplicity and minimalism; an obsession with getting things right, even if that took more time and considerably more resources; a very strong and highly polarized opinion about anything coupled with the ability to change his opinion if convinced; strong self-belief; showmanship; ability to communicate and connect with an audience; the ability to “distort reality,” to make people think they could do “impossible” things in crazily ambitious timeframes; the perspective to combine art and technology to create well designed, high technology products for (a relatively affluent?) mass market.

Where did these attributes and skills come from? Was Jobs simply born with them, or did he develop these along the way? And, what external influences played a role in this process?

The Source of Steve Jobs’ Genius

Steve Jobs’ (adopted) father Paul Jobs re-conditioned old cars and then sold them. He had a workshop at home where he spent hours in various mechanical activities. Paul also built anything needed for their home, from cupboards to a fence, himself. Steve learnt the importance of craftsmanship and focusing on the details from Paul. Steve’s obsession that whatever is invisible to the customer should be as perfectly designed and executed as what is visible had its origins in Paul Jobs’ attitude towards his own work.

Steve’s practical bent was helped by his early exposure to Heathkits (“do-it-yourself” kits for electronic products and amateur radios), membership of the HP Explorers’ Club, and an electronics class at school where students were encouraged to tinker around with a variety of electronics components. An area in which Steve exercised his ingenuity was in playing pranks on fellow students and teachers, leading to several punishments by his school. Jobs’ first “business” came from trying to “fool” the telephone system into making long-distance calls for free by simulating the tones that routed signals on the phone network, and then selling the box that allowed him to do this. (The box itself was designed by Steve’s friend and Apple co-founder, Stephen Wozniak, as were many other gadgets including the Apple II computer).

Steve had a spiritual side to him from an early age. This appears to have been partly driven by his endeavor to come to terms with his biological parents giving him up for adoption, and partly was a function of the times – Steve was a teenager in the late 1960s, a time of great political and social ferment in the US. This was the time of the anti-Vietnam protests, an interest in Indian spirituality and culture. This is when Ravi Shankar became famous, and the Beatles embraced Mahesh Yogi!. Steve spent several months in India connecting with different spiritual leaders, and this was the start of a lifetime interest in Zen Buddhism. His belief in simplicity and minimalism, and his ability to maintain a laser-like focus on a few priorities had strong links to this interest.

Isaacson quotes Jobs as saying, “I began to realize that an intuitive understanding and consciousness was more significant than abstract thinking and intellectual logical analysis” (p. 35).

Steve dropped out of college after a year because he didn’t like the regular routine and the mix of subjects he had to study. But the college allowed him to continue to attend courses of his interest for some time. It was during his stay at Reed College that he developed his lifelong interest in calligraphy (which played a big role in the graphics capabilities of the Macintosh), and took basic courses in design.

Why India won’t have a Steve Jobs

Very few of us in India do things with our hands. “Brahminical” India consistently ranks the brain and intellect over the hands and creative skills. So much so that even people from traditional craft backgrounds want to flee to white collar vocations. How many of us grow up with a workshop in our homes? No Paul Jobs-like inspiration is likely in our immediate environs…

Most Indian families would shudder at the kind of unstructured experiences that a young Steve Jobs had. Hanging around in another country for months in the quest of a spiritual experience? I can’t imagine anyone I know allowing their children to do that. And this is not a financial issue. So many of my friends and acquaintances are spending upwards of $200,000 educating their children in the US or UK. But they would go apoplectic if their children were to take a “break year,” let alone get an unstructured experience of the Steve Jobs type.

I was recently chatting with the fellows at Ashoka University’s Young India Fellowship (YIF) Programme, an exciting postgraduate, liberal arts / critical thinking-oriented education initiative created by my good friend Pramath Raj Sinha. I was surprised to learn from many of them that they had a tough job convincing their parents that YIF was a worthwhile investment of their time! Recently, one of my acquaintances, a senior manager in a leading multinational decided to cycle from Bangalore to Hubli – by his own account, his mother and brother made a considerable effort to dissuade him from doing any such thing. I am sure everyone has heard similar stories or faced related experiences…

Our whole system pushes people towards conformism. A good friend, HR head of a leading multinational, proudly told me over dinner recently that HR is good at getting people “in line.” And snuffing out enterprise in the process?

Are things changing? I was enthused to read about Akhil Mohan, a young student, who has become a passionate advocate of conservation after an interactive trip with the Bishnoi tribe in Rajasthan. But, how many of our young students get exposed to such experiences?

Conclusion

Of course, Steve Jobs’ success was not due to his individual genius alone. He grew up in the right place at the right time – Silicon Valley in the late 1970s was the centre of the personal computer revolution. As Amar Bhide pointed out so eloquently in The Venturesome Economy, customers in the US have shown a proclivity to try out products from unknown entrepreneurs that is perhaps unmatched elsewhere. The US is certainly a more conducive place to do business than India – in Isaacson’s book, you won’t come across a single one of the typical constraints that a company in India faces. Steve’s colleagues and employees at Apple, Next and Pixar seem to have put up with a lot of his bad behavior, and I am amazed that in a country as litigious as the US, he got away with all this without a significant lawsuit against him

Of course, Steve Jobs’ success was not due to his individual genius alone. He grew up in the right place at the right time – Silicon Valley in the late 1970s was the centre of the personal computer revolution. As Amar Bhide pointed out so eloquently in The Venturesome Economy, customers in the US have shown a proclivity to try out products from unknown entrepreneurs that is perhaps unmatched elsewhere. The US is certainly a more conducive place to do business than India – in Isaacson’s book, you won’t come across a single one of the typical constraints that a company in India faces. Steve’s colleagues and employees at Apple, Next and Pixar seem to have put up with a lot of his bad behavior, and I am amazed that in a country as litigious as the US, he got away with all this without a significant lawsuit against him

But it seems clear to me that as long as we cloister and mollycoddle our youngsters, and prevent them from having a wider range of influences and experiences, our chances of ever producing a Steve Jobs from India are very dim indeed.

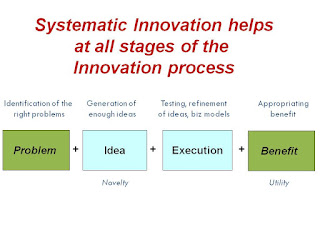

ian companies need to embrace systematic innovation so as to capitalize on their innate abilities of intuition and market sensing. Vinay Dabholkar and I hope that 2013 will be the year for systematic innovation in India. May systematic innovation go viral! Our own contribution towards this will be released soon – watch this space for more details!

ian companies need to embrace systematic innovation so as to capitalize on their innate abilities of intuition and market sensing. Vinay Dabholkar and I hope that 2013 will be the year for systematic innovation in India. May systematic innovation go viral! Our own contribution towards this will be released soon – watch this space for more details!