This article is based on the book Platform Scale, written by Sangeet Paul Choudary. Platform Scale is available for free download for a limited period between October 5th and October 9th. To access additional bonus content, check the book website here.

The on-demand economy is bringing together technology and freelance workers, to deliver us services in exciting new ways. We are increasingly using our cell phones as a remote control for the real world.

Every week, we see a new platform come up that connects consumers with freelance labor. New companies are forming in almost every service vertical. But not all these companies clearly understand what determines success and failure of on-demand business models.

Success in the On-demand economy

There are two critical factors that will determine the success of a company in the on-demand economy: multihoming costs and interaction failure.

MULTIHOMING COSTS

In computer networking parlance, mutihoming refers to a computer or device connected to more than one computer network. In the world of platforms, this notion is an important one. If your producers and/or consumers can co-exist on multiple platforms, you face a constant competitive threat. Eventually, it may be difficult for clear winners to easily emerge.

Multihoming costs are relatively high for developers to co-develop for both Android and iOS. Multihoming costs are high for consumers also because of the cost of mobile phones. Most consumers will own only one. However, multihoming costs for drivers to co-exist on Uber and Lyft are relatively low. Most drivers participate on both platforms. Given the ease of booking rides, multi-homing costs are very low on the consumer side as well.

In a previous article on TechCrunch, I had elaborated in detail how multi-homing could be prevented by creating long-term stored value within the platform.

For on-demand platforms, this is important because multihoming allows producers (service providers) to co-exist on multiple platforms. With a limited supply of service providers available, this can lead to interaction failure.

INTERACTION FAILURE

Interaction failure happens when the producer or consumer (or both) participate(s) in an interaction, without the interaction reaching its logical, desired conclusion. Imagine a merchant setting up a listing on Ebay that never gets any traction, or a video enthusiast uploading a video on YouTube that fails to get a minimum number of views. Quite often, these outcomes could be the result of poor quality listings or videos, but they could also be owing to the platform’s inability to find the right matches. Producers and consumers who experience interaction failure get discouraged from participating further and abandon the platform.

If reverse network effects set in, this can eventually lead to an implosion of a platform. In the initial days, interaction failure regularly leads to the chicken and egg problem. To understand these phenomena better and how they could impact your platform, I’d recommend this post on reverse network effects and this one on the chicken and egg problem.

Bringing it together – The Uber-Lyft war

Interaction failure is especially important for on-demand platforms. Imagine a consumer requesting for a service and the service never arriving. Imagine, in turn, a producer receiving a request, preparing to fulfill that request, only to find that the request gets cancelled. In both cases, the consumer or the producer may decide to abandon the platform.

This is exactly what Uber had in mind when it waged its war on Lyft. Unethical as that was, I’d like to focus on that to glean lessons for building the next Uber for X.

In some of the largest cities we see drivers drive for both Uber and Lyft, and other competitors. It’s not uncommon for these drivers to switch between the two platforms multiple times a day. With a limited supply of drivers in a city and the cost for a driver to connect to an additional platform so small, we see drivers multihoming on both Uber and Lyft. This has naturally led to intense competition between the two companies and Uber infamously resorted to a playbook to create interaction failure on Lyft using questionable tactics.

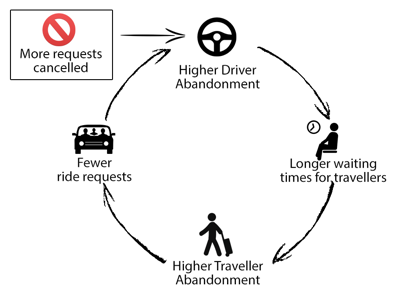

Uber decided to target interaction failure on Lyft, by contracting third party employees to use disposable phones to hail Lyft taxies. Before the Lyft taxi arrived at its pickup location, the Uber contracted employee would cancel the ride. With so many cancelations on the Lyft platform, drivers would become frustrated driving for Lyft and, in some cases, switch over to Uber. Lower drivers would lead to further frustration for consumers as they would have to wait longer for their requests for cabs to be fulfilled, eventually spurring them to abandon the platform. This loop is illustrated below.

When multihoming costs are low, producers and consumers will connect to many platforms. With multiple platforms sharing the same producers and consumers, it is difficult for a business to build defensible networks. Thus, it is difficult for a clear winner to emerge in the market. With many platforms operating and defensibility low, interaction failure becomes a key factor in determining long-term winners.

What does this mean for you?

If you’re building the Uber for X, you need to ensure that you’re tracking a metric that helps you determine the degree of interaction failure on your platform. Freelancers that don’t get business within X days, requests that don’t get satisfied within Y minutes, may all be indicative of interaction failure. The exact measure of interaction failure will vary by platform and the importance of tracking interaction failure will, in turn, depend on the multihoming costs.

If you’re building the Uber for X, you need to ensure that you’re tracking a metric that helps you determine the degree of interaction failure on your platform. Freelancers that don’t get business within X days, requests that don’t get satisfied within Y minutes, may all be indicative of interaction failure. The exact measure of interaction failure will vary by platform and the importance of tracking interaction failure will, in turn, depend on the multihoming costs.

About the author: Sangeet Paul Choudary is the author of the book Platform Scale, available for free download for a limited period between October 5th and October 9th. He also writes the blog Platform Thinking.