The much-hyped Goods and Services Tax (GST), after years of stagnation and lack of political consensus, was finally passed in the upper house of the Parliament, the Rajya Sabha, on 4th August this year, almost a decade after it was first introduced in the Lok Sabha in the year 2006-07. It is the biggest indirect tax reform post economic liberalization of 1991.

The economists say, a double-digit growth in GDP, which seemed too surreal, will now be a reality. This law aims to give a boost to the new age start-ups and make India a conducive place to conduct business. Currently, India is home to around 4,200 startups growing at an exponential rate of 40% yearly. It is predicted that, with further relaxation of rules, India will be home to around 11,000 startups by 2020. This can be corroborated by the fact that India was ranked poorly at 142nd in the ‘Ease of Doing Business’ survey conducted by the World Bank in 2015. With relaxation in the rules and regulations of setting up a business and lucrative schemes like ‘Start-up India, Stand up India’, India went twelve places up and ranked at 130 in 2016.

Before getting into the nitty-gritty of how beneficial will the new law be for startups, it is important that the basics of this law are first looked into. GST, as mentioned above, is an indirect tax reform also known by the moniker – ‘One India, One Tax’. Different states have different tax structures which make the taxation structure very cumbersome and complex. This is a major reason why many start-ups are hesitant to expand their businesses to different states leaving the state concerned with little industrialization and low creation of jobs. GST aims to bridge the gap by integrating all taxes, making only one tax to be paid by everyone. As a result, the tax calculations will be simpler, saving time and energy for entrepreneurs and start-ups to focus on their respective businesses instead of investing time and energy on compliance and paperwork. However, just passing the bill is not the end of the story – there are rules to be framed, tax rates to be fixed, the central and state governments must reach a consensus, and proper infrastructure needs to be put in place. Hence, the implementation of GST still has a long way to go and is likely to happen in mid-2017.

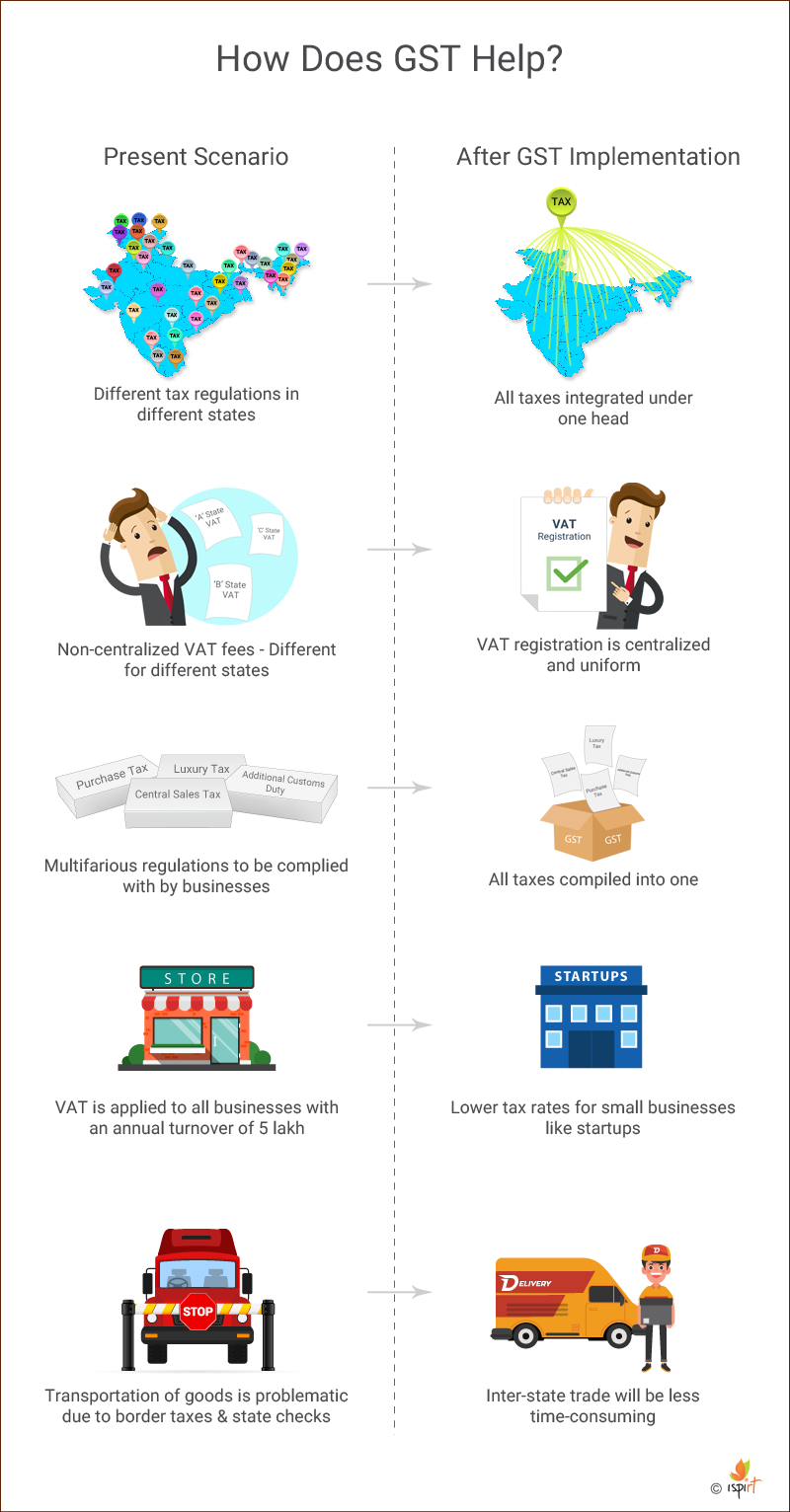

How Does the GST Help?

The Act is deemed to benefit all types of businesses but start-ups and SMEs are to benefit the most. It has been structured in a way keeping in mind the concerns of the small businesses. This is elaborately explained in points mentioned below –

Simple Taxation – Instead of adhering to different tax regulations in different states, GST simplifies the process by making it simpler and clear by integrating all taxes into one so that not only money on taxes are saved but time on compliances are saved too.

Ease of Conducting Business – Registration of VAT from the sales tax department of the state concerned is an imperative to start a new business. A business intending to establish in different states has to apply for VAT registration separately. Not only this, the VAT fees in different states is not uniform, making this one among the many other issues regarding the problems faced by startups and existing businesses in India. To fix this anomaly, the GST Act has provisions which will make VAT registration centralized, uniform and simple for companies. The concerned company/business would just need to get a single license valid pan India and pay taxes regularly. This will further help startups to establish, expand their business hassle-free.

Integration of Multiple Taxes – In addition to the VAT and service tax, there are other tax regulations that must be complied by the businesses like Central Sales Tax, Luxury Tax, Purchase Tax, Additional Customs Duty etc. Upon the implementation of the GST, all such taxes will be combined into one.

Lower Tax Rates for Small Businesses – At present, VAT is applied to businesses having an annual turnover of INR 5 lacs and above. GST aims to cap this limit to INR 10 lacs only and businesses with turnover between INR 10-50 lacs will be taxed at low rates. This move will not only bring respite to the start-ups but also help them invest the money saved on taxes back in their business.

Improvement in Logistics efficiency – Seamless movement of goods is currently a problem with border taxes and checks at state borders which delay the movement of goods which, in turn, results in delayed deliveries and enhances the product cost. GST aims to eliminate such inefficiencies making the inter-state trade less time consuming. With an uninterrupted movement of goods across the border, the costs associated with maintaining the goods will significantly reduce. According to a CRISIL analysis, the logistics cost of non-bulk goods can go down by as much as 20% once GST is implemented.

Other Side of GST: The Cons

While there are other advantages for the start-ups as well other than the ones mentioned above, the new Act also comes with implications, not necessarily for the start-ups. Start-ups in the manufacturing sector with lesser turnovers might have to bear the brunt of paying duty. As per the existing excise laws, any manufacturing business with an annual turnover of less than INR 1.5 crores is exempted from paying duties. But when the GST comes into force, the chances are, this limit could be reduced by six times to INR 25 lacs. This can have a detrimental effect on the growth of start-ups.

There are high chances that the inflation might rise after GST implementation. Also, whether ‘mandi tax’ would be included or not in the GST is ambiguous. Such causes can adversely affect the food startups.

Critics also say, the implementation of GST would also affect the real estate business and add up to 8% of the cost in new homes and as a ramification thereof, reduce the demand by 12%.

Despite its implications, GST is the most important and business friendly tax reform in India which will lead to a double-digit growth. It seeks to unify, integrate different tax structures so that there will be transparency and efficiency in the way businesses operate and the government levies taxes. This won’t just reduce the cost of the products but also create employment opportunities as more startups rise and India becomes the startup capital of the world!

Guest post by LegalDesk.com, a Do-It-Yourself legal platform for making legal documents online. LegalDesk helps startups with incorporation and legal documentation services. It also provides Aadhaar-based eSign service to businesses.