The distinction between whether you are building a platform or a product should be made primarily to align your internal stakeholders to a particular strategic direction, as we learned in the recent iSPIRT round table.

[This is a guest post By Ben Merton]

“So are we a platform, or are we a product?” I said last month to my co-founder, Lakshman, as we put the finishing touches to our new website.

We’d been discussing the same question for about a year. The subject now bore all the characteristics of something unpleasant that refuses to flush.

However, the pressure had mounted. We now had to commit something to the menu bar.

“I think we’re a product.”

“But we want to be a platform.”

“Okay, let’s put platform then…But isn’t it a little pretentious to claim you’re a platform when you’re not?”

Eventually, we agreed to a feeble compromise: we were building a platform, made up of products.

Job done.

At least, that is, until #SaaSBoomi in Chennai last month.

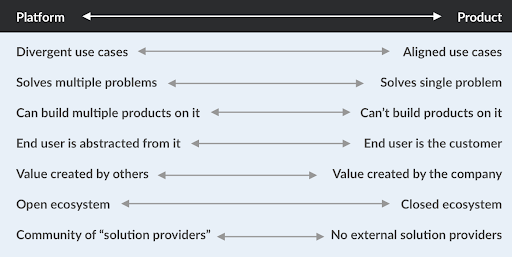

Manav Garg, who has considerably more experience than both me and Lakshman at building platforms, put up the following slide:

Product = Solving a specific problem or use case

Platform = Solving multiple problems on a common infrastructure

“Here we go again”, I could hear Lakshman say to himself after I Whatsapped him the image.

“That’s his definition. It doesn’t have to be ours,” he replied tersely, “What does he mean by ‘use case’, anyway?”

“I don’t know.”

I’m in awe of the entrepreneurs who seem to bypass these semantic quandaries.

You know, the ones who say stuff like “Stop thinking so much. Just sell stuff. Make customers happy.”

For me, these are the type of questions I need to chew over for hours in bed at night.

I was therefore excited to be invited to the iSPIRT round table at EGL last week, where the topic of discussion was “Transform B2B SaaS with #PlatformThinking”. The roundtable was facilitated by iSPIRT mavens Avlesh Singh, Shivku Ganesan & Sampad Swain.

It takes a lot to get 20 tech founders & their leaders to travel after work from all over the city to sit in a room for three hours with no alcohol. Fortunately, the organisers had promised a lot. The topic description was:

“Enable a suite of products, high interoperability, and seamless data flow for customers. This peer-learning playbookRT will help product to platform thinkers develop an effective journey through this transformation” was the topic description.”

The meeting was governed by Chatham House rules, meaning we can’t discuss the name or affiliation of those involved.

However, along with our founder mavens of large, well-known Indian technology businesses, there were 15 or so less illustrious but equally enthusiastic founders (& their +1s), including myself.

The discussions started with an overview of the experiences and lessons that had been learned by some of those who had successfully built a platform.

“We define a use case as a configuration of APIs…” the founder of a cloud communication platform started. This was going to be interesting.

“Why did you define it that way?” I asked.

“Based on observations of our business.”

I began to understand that the term ‘use case’ was being used differently by platform and product companies.

“A use case of a platform is usually tangential but complementary to the core business. A use case for a product is something that just solves a problem,” someone clarified, guaranteeing me a slightly more restful night.

As the discussions continued, it also became clear that there were a large number of possible markers that distinguish a platform from a product, but there was no agreement on the exact composition.

To resolve the impasse, we listed out the names of well-known technology companies to build a consensus on whether they were a platform or a product.

Suffice to say, we failed to reach any consensus. The conversation went something like this:

“Stripe?”

“Platform.”

“Product.”

“A suite of products.”

“AirBNB?”

“A marketplace.”

“A marketplace built on a platform.”

Etc etc

Even companies that initially appeared to be dyed-in-the-wool platforms like Segment and Zapier eventually had someone or the other questioning the underlying assumptions.

“Why can’t they be products?” murmured voices of dissent at the back of the room.

This was going nowhere. A few people sought solace from the cashew nuts that had been placed on conference table in front of us.

“Does the customer care whether you’re a product or a platform?” someone said.

Finally, something everyone could agree on. The customer doesn’t care. Your product or platform just needs to solve a problem for them.

“Then why does any of this matter at all?” became the obvious next question.

“I found it mattered hugely in setting the direction of the company, especially for the engineering and design teams,” the Co-Founder of a large payment gateway said.

“And investors?”

“Yes, of course. And investors. However, I think the biggest impact that our decision to build a platform had on my business was in the design more than anything else,” he explained, “For the engineering team, it was just a question of ‘we need this to integrate with this’. But the UX/UI and the…language… needed to be thought about very carefully because of this decision.”

“So, in effect, the platform/product debate is primarily a proxy for the cultural direction of the company?”

“Exactly.”

Logically, therefore, the only way you can really understand whether a company is a platform or a product is to have an insight into the direction its management wishes to take it.

A company might appear to be a product from the outside but, since it intends to evolve into a platform, it needs to start aligning its internal stakeholders to this evolution much earlier.

“So, a startup like mine should call itself a platform even if we are years away from actually being one?” I asked cautiously after I had enough time to process these insights.

“Yes,” was the resounding, satisfying response that virtually guaranteed me a full night’s sleep.

“And when should the actual transition from product to platform happen?”

“Well, Jason Lemkin says it should happen only when your ARR reaches USD 15m-20m, but that’s just another of those rules that doesn’t apply in India,” the co-founder of a marketing automation software said.

“The important thing is that this transition – when it does happen – is very hard for businesses,” he continued, “There is a lot of risk, but it opens up new revenue streams, helps you scale and build a moat. We hugely benefited from our decision to become a platform, but it was tough.”

It’s unlikely that we completely resolved the product vs platform debate for all founders. However, I feel that all of us came away from that meeting with a deeper insight into the subject.

Ultimately, whether you’re building a product or a platform will depend on your perspective. Most companies lie somewhere in between.

Where does your company lie on this sliding scale? And if that makes you a platform vs. a product, does it make any difference to the way you think?

We want to thank Techstars India for hosting the first of the roundtables on this critical topic.

Ben Merton

Ben is a Co-Founder of Unifize, a B2B SaaS company that builds a communication platform for manufacturing and engineering teams. He is also a contributor for various publications on business, technology and entrepreneurship, including the Wall Street Journal, the Financial Times and Business Standard. You can follow him on LinkedIn here, and Twitter here.

© Ben Merton 2018

Featured Image: Source: https://filosofiadavidadiaria.blogspot.com/2018/01/o-principio-mistico-da-verdadeira-causa.html