As you may have heard from us or read about in our publications, iSPIRT takes the long view on problems. We call ourselves 30 year architects for India’s hard problems. The critical insight to a 30-year journey of success is that it requires one to be able to work with and grow the ecosystem, rather than grow itself. An iSPIRT with more than 150 volunteers would collapse under its own weight. Instead we work tirelessly to build capacity in our partners and help them on their journeys. We remain committed to being in the background, taking pride in the success of our partners who are solving for India’s hard problems.

However, many people think we’re trying to square a circle here. Why would anybody, that too, folks in Tech jobs who get paid tremendously well, volunteer their time for the success of others?

The motivation for volunteering is hard to explain to those who have not experienced the joy volunteering brings. Our story is not unique. Most famously, when the Open source movement was taking root, Microsoft’s then CEO, Steve Ballmer, called Open Source “cancer”.

We have published all of our thinking on our model as and when it crystallised. However, we realised a compendium was needed to put our answers to the most commonly expressed doubts about iSPIRT in one place. This is that compendium for our volunteers, partners, donors and beyond.

1. What is iSPIRT?

a) iSPIRT is a not-for-profit think tank, staffed mostly by volunteers from the tech world, who dedicate their time, energy and expertise towards India’s hard problems.

b) iSPIRT believes that India’s hard problems are larger than the efforts of any one market player or any one public institution or even any one think-tank like ourselves. These societal problems require a whole-of-society effort. We do our part to find market players and government entities with the conviction in this approach and help everyone work together.

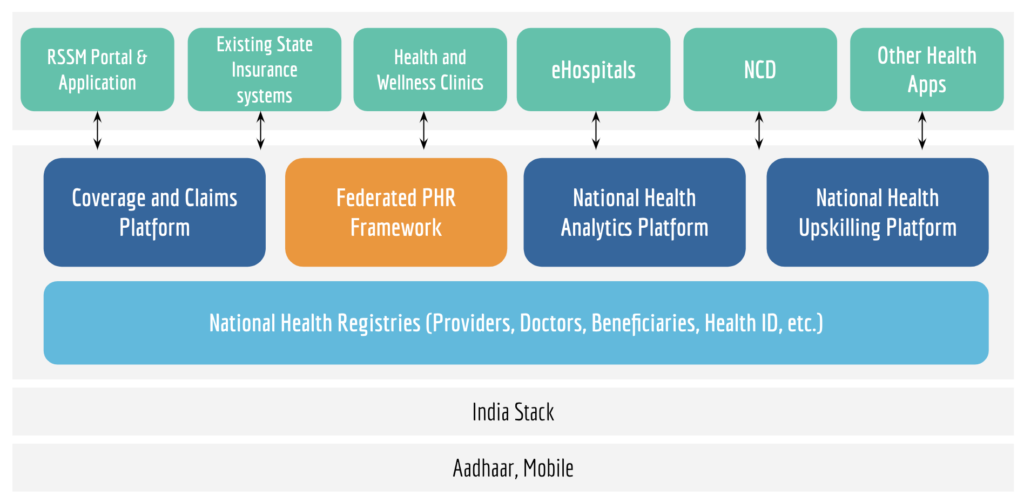

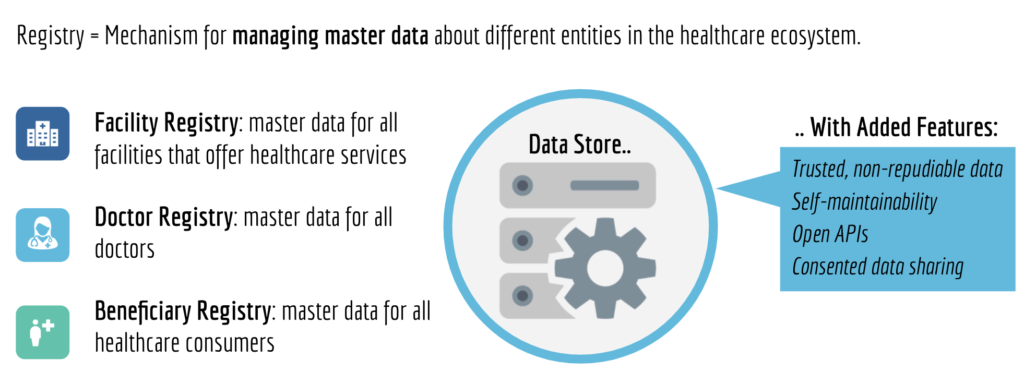

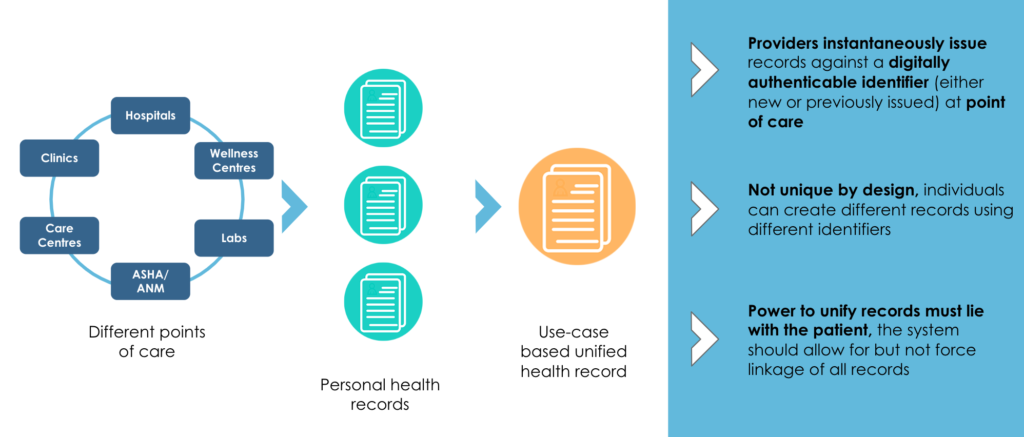

c) In practical terms, this means that the government builds the digital public infrastructure, and the market participants build businesses on top of it. We support both of them with our expertise. We have iterated this model and continue to improve and refine this model.

d) To play this role we use our mission to align with the Government partners, Market partners and our own volunteers. We believe those who have seen us work up close place their trust in us to work towards our mission. Our long-term survival depends on this trust. All our actions and processes are designed to maintain this trust, and so far if we have any success at all, it can only be seen as a validation of this trust.

2. What is our volunteering model?

a) Anyone can apply to be a balloon volunteer, and we work with them to see if there is a fit.

b) The ideal qualities of a volunteer are publicly available in our Volunteering Handbook, the latest one was published in December 2017.

c) We require every volunteer to declare their conflicts, and ask them to select a pledge level. This pledge level determines their access to policy teams and information that can lead to potential conflict of interest. For every confirmed volunteer, we make available this pledge level publicly on our website.

d) We are often asked what’s in it for our volunteers. We let all our volunteers know this is “No Greed, No Glory” work. Wikipedia is maintained by thousands of volunteers, none of them get individual author credits. What volunteers get is the joy of working on challenging problems a sense of pride in building something useful for society a community of like-minded individuals who are willing to work towards things larger than themselves

e) There are not too many people who would do this for no money, but it does not take a lot of people to do what we do. All of this is given in much greater detail in our Volunteer Handbook.

3. How does iSPIRT decide the initiatives it works on?

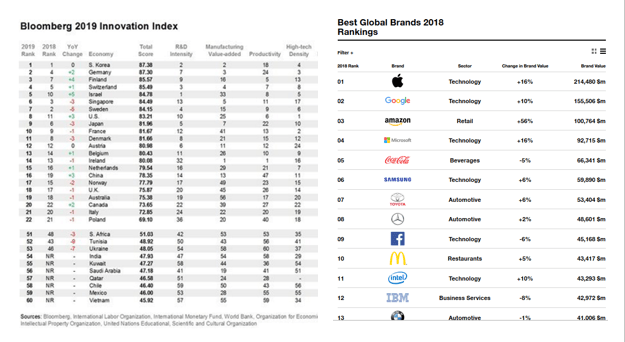

a) We have seen success due to the quality of our work and the commitment to our mission. We only take on challenges related to societal problems where technology can make a difference.

b) Even within those problems, our expertise and focus is in solving the subclass of problems where the hard task of coordination between State and Market, between public infra and private innovation is crucial to the task at hand.

4. How does it work with State and Market partners

a) On the hard problems we select in #3 above we assemble a team of volunteers. These volunteers outline a vision for the future. We begin by sharing this vision in multiple forums and creating excitement around them. Examples of these forums are:

- 2015: Whatsapp moment of India. Nandan Nilekani presentation on the future of finance and many articles written about it

- 2016: Startup India Launch – Jan 2016 13th. India Stack unveiled as part of official program of Digital India (Public event)

- 2017: Cash Flow Lending – DEPA launch 2017 August – Carnegie India Nandan Nilekani and Siddharth Shetty Presentation

- Many different public appearances by Pramod Varma, Sharad Sharma, Sanjay Jain, Nikhil Kumar

- 2019: Siddharth Shetty explaining AA at an event at @WeWork Bangalore

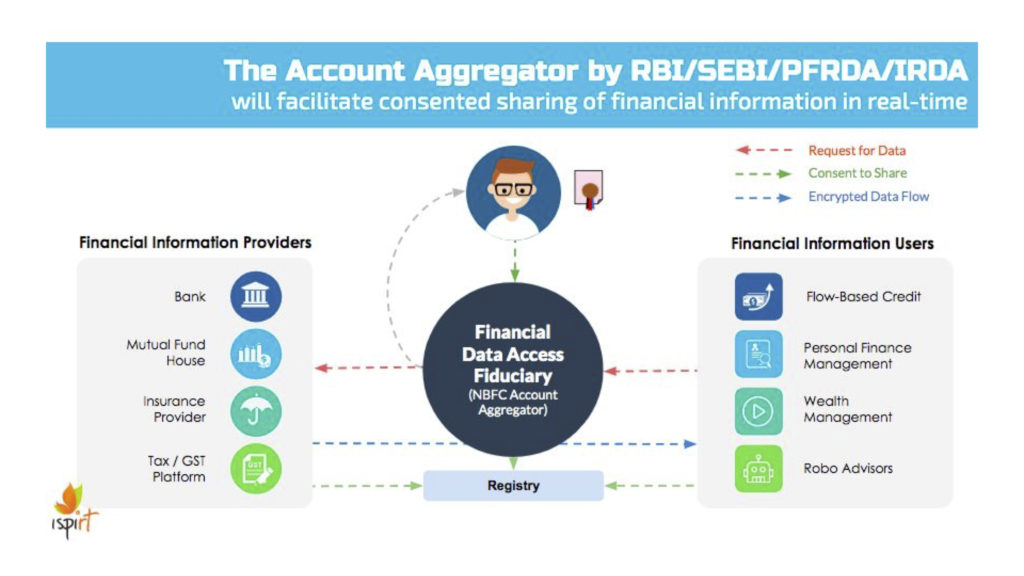

- 2019 Sahamati Launch with a presentation by Nandan Nilekani and representatives from MeiTY, SEBI, multiple Bank CEOs, and AA entrepreneurs.

b) On market partners

i. We work with any market partner who shows conviction towards the idea, and are willing to commit their own resources to take the vision forward. Previous and current partners include banks, startups, tech product and service companies. These early adopter partners form part of our Wave 1 cohort.

ii. We dive deeper with this wave 1 cohort and iterate together to build on the “private innovation” side of the original vision with their feedback. This is developed with the mutual commitment to sharing our work in the public domain, for public use, once we have matured the idea. We work with them and iterate till we surface a MVP for wider review.

iii. At iSPIRT, we don’t like mission capture. There are no commercial arrangements between iSPIRT and any individual market participants.

iv. We never recommend specific vendors to any of our partners.

v. New infrastructure/ new frameworks often require the creation of a new type of entity. We engage with these through domain specific organizations such as Sahamati for Account aggregators, as an example.

vi. After Wave 1 partners co-create an MVP, we open up for wider public review and participation. We make public all of our learnings to help the creation of Wave 2 of market participants.

vii. The mental model you should have for iSPIRT Vision/Wave 1/ Wave 2 is those of Alpha/closed Beta/public Beta in the tech world.

c) On government partners

i. We work together with any government partners who show conviction towards the idea, and are willing to commit their own resources to take the vision forward. Previous partners have been RBI, NPCI, MeiTY, TRAI, etc.

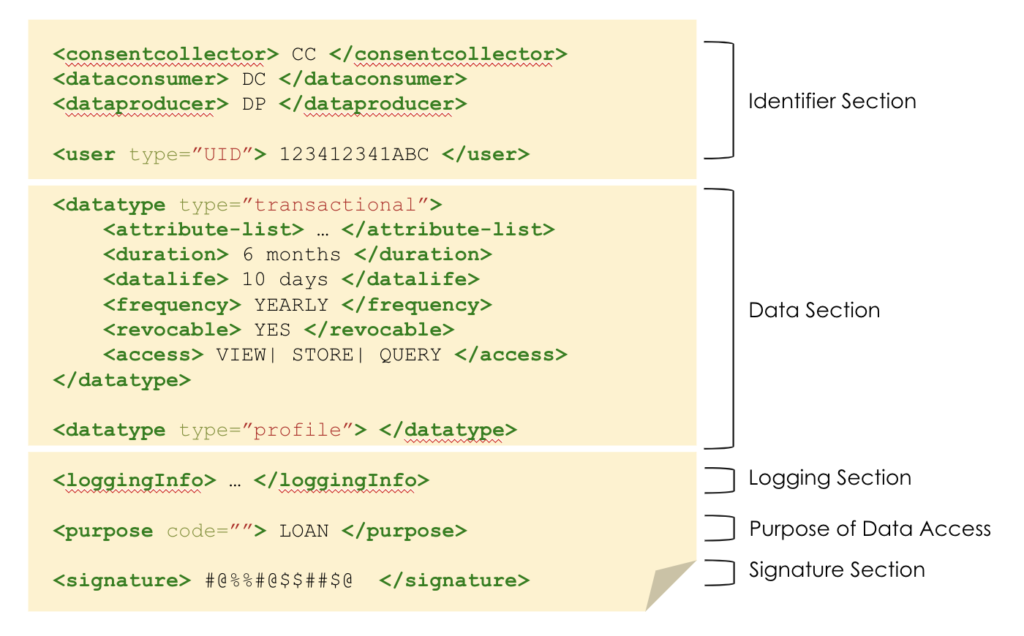

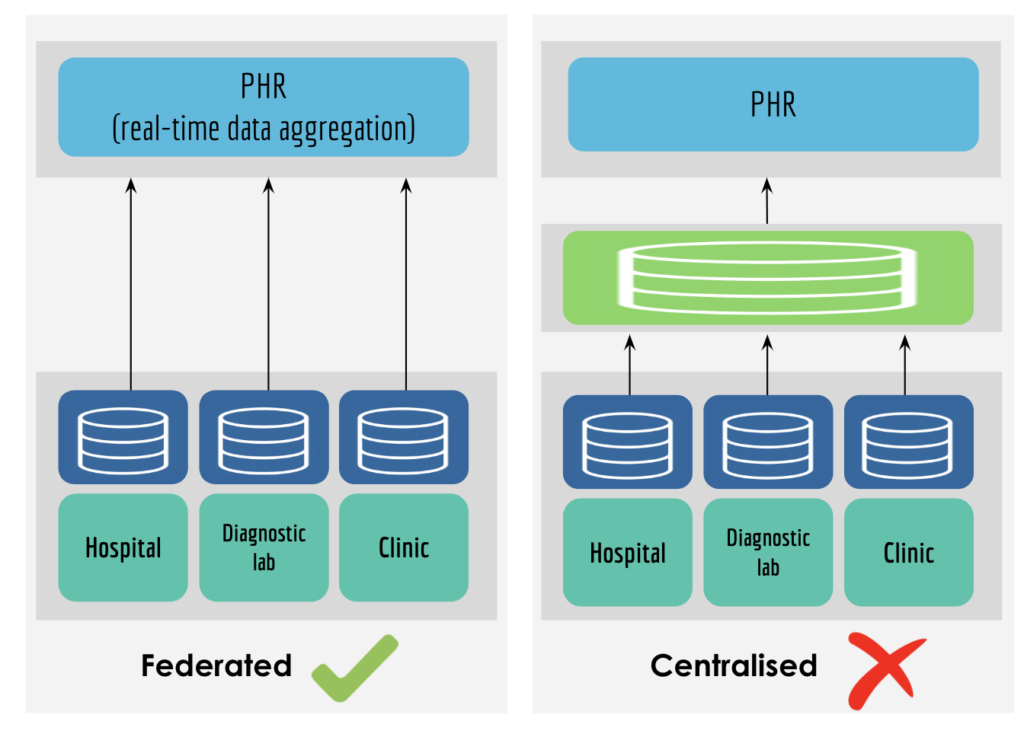

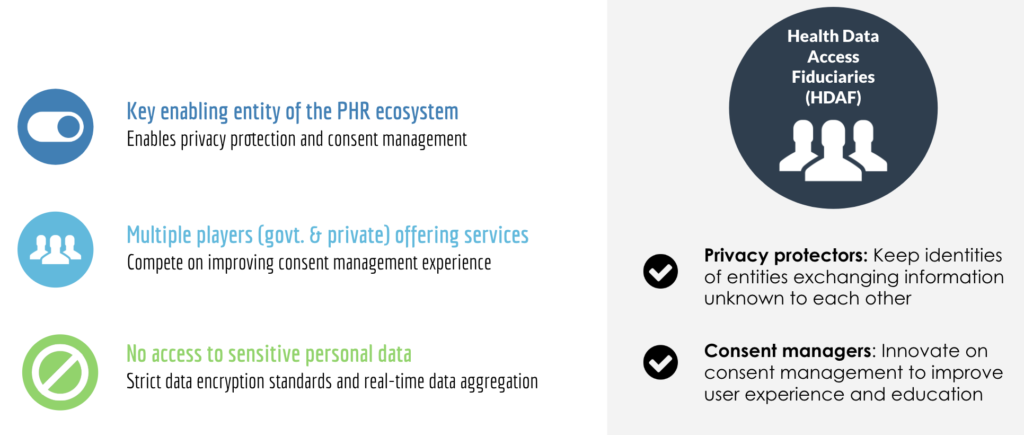

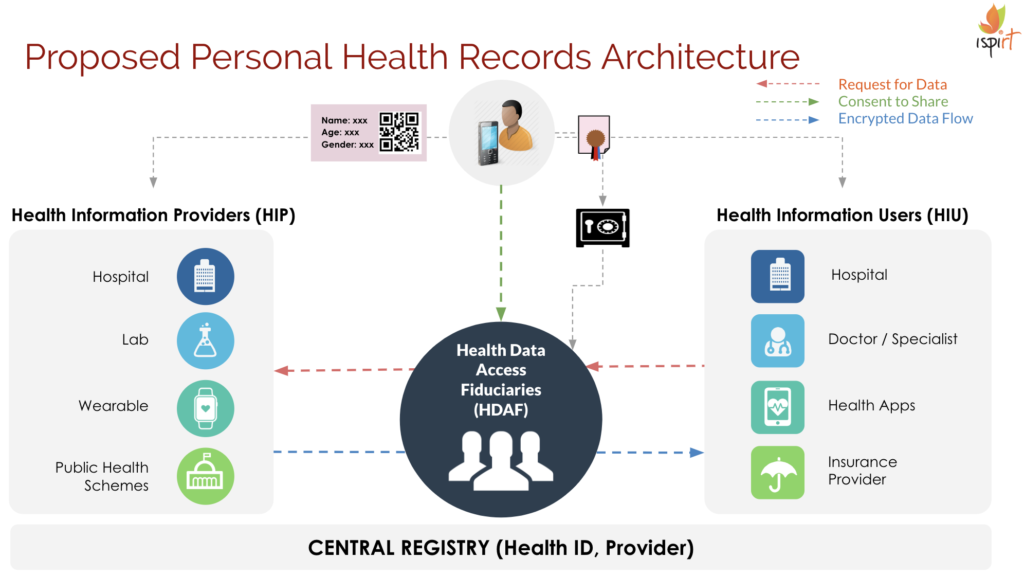

ii. We dive deeper with these partners and iterate together to build on the “public infrastructure” side of the original vision with their feedback. As part of the government process, many authorities have their own process to finalize documents, etc. Many of these involve publishing drafts, APIs etc. for feedback, and potential improvement from market participants. We publish the work we do together and invite public comments. Examples: UPI Payment Protocol; MeITY Electronic Consent Artefact; ReBIT Account Aggregator specifications

iii. We only advise government partners on technology standards and related expertise.

iv. There are no commercial arrangements between iSPIRT and government partners, not even travel expenses.

v. We never recommend any specific market players for approval towards any licenses or permissions. Both iSPIRT and our partners would suffer greatly if this process was tarnished.

- With UPI we did not recommend any individual PSPs for inclusion in the network. This was entirely RBI and NPCI prerogative.

- Similarly for AA, RBI alone manages selection of AAs for approvals of licenses.

vi. We also respond to public comments wherever they are invited. The following are some examples of our transparent engagement on policy issues.

- iSPIRT Public Comments & Submission to Srikrishna Privacy Bill

- iSPIRT Public comments to TRAI Consultations

- Support to RBI MSME Committee Report

- Support to RBI Public Credit Registry Report

5. How does iSPIRT make money?

a) iSPIRT’s expenses includes a living wage for some of its full-time volunteers, travel expenses and other incidental expenses related to our events. This is still a relatively small footprint and we are able to sustain entirely on donations.

b) These donations come from both individuals and institutions who want to support iSPIRT’s long-term vision for India’s hard problems. Sometimes, donor institutions include our market partners who have seen our work up close.

c) Partnerships do not require donations. We engage with many more market partners who are NOT donors than donors who are market players.

6. How does iSPIRT protect against conflict of interest?

We see two avenues of conflict of interest, and have governance mechanisms to protect against both

a) First is Donor Capture. We try to structure donation amounts and partners such that we are not dependent on any one source of funds and can maintain independence

i. We maintain a similar separation of concerns as do many news organizations with their investors.

ii. Our volunteers may have a cursory knowledge of who our donors are. However, this knowledge makes no difference to their outcomes.

b) Second is Volunteer conflicts, where they may get unfair visibility or information to make personal gains.

i. We screen for this risk extensively in the balloon volunteering period.

ii. We have hard rules around this that are strictly enforced and constantly reminded to all our volunteers in all our meetings.

iii. For volunteers who need advice whether a potential interaction could constitute conflict we provide an easy avenue through our Volunteer Fellows Council. The council will advise on whether there is conflict and if yes, how to mitigate it.

iv. To prevent a “revolving door” situation, we require that volunteers from the policy team leaving to continue their careers in the industry undergo a “cooling-off” period.

To volunteer with us, visit: volunteers.ispirt.in

The post is authored by our core volunteers, Meghana Reddyreddy and Tanuj Bhojwani. They can be reached at [email protected] and [email protected]