- Context

- Format

- Ideas & Themes

- Speakers & Judges

- Event Calendar

- Sponsors & Partners

- Prizes

- Registration Details

Context

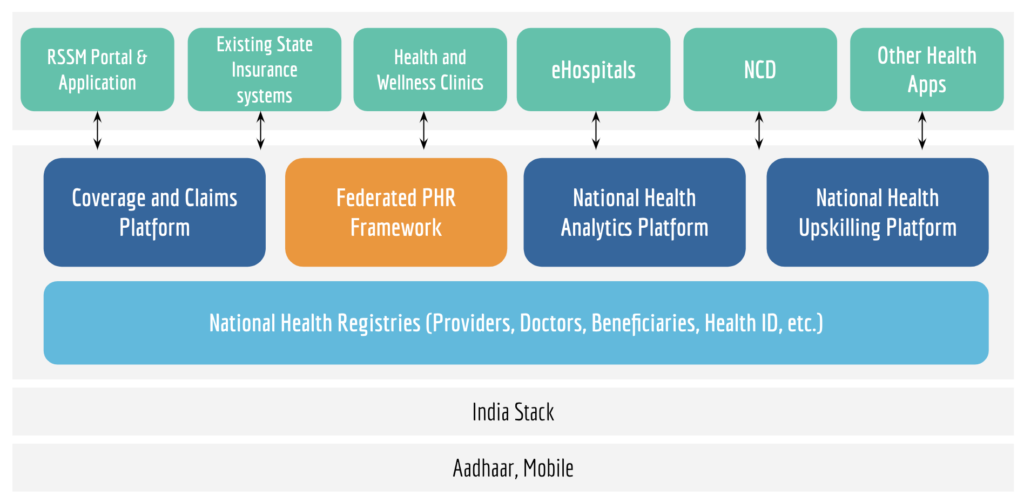

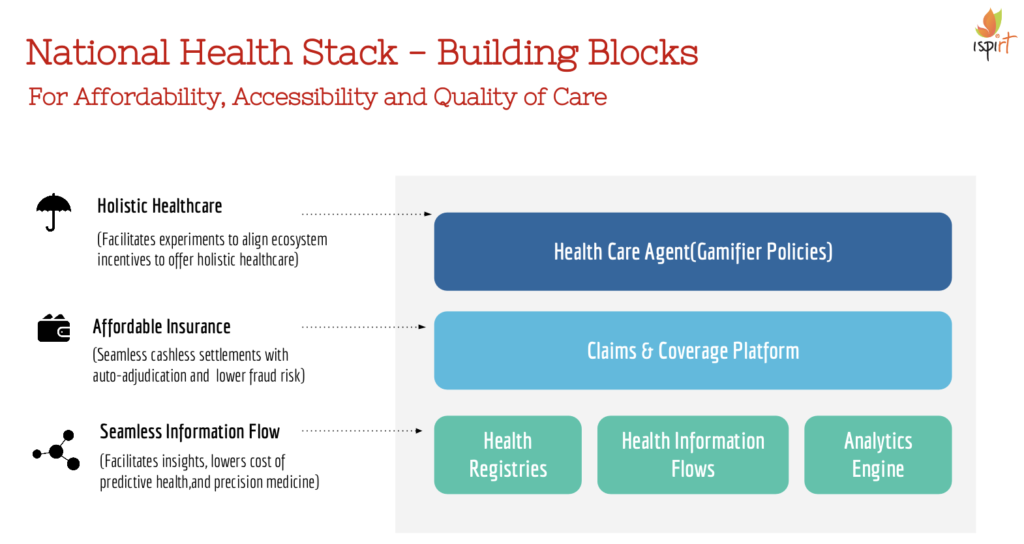

Those of you who have been following this blog would know that as we speak, India is rolling out a piece of public digital infrastructure known as the National Health Stack (NHS). This project, which is being put into place to futurize the nation’s health technology ecosystem, has exciting and important ramifications for the entire country.

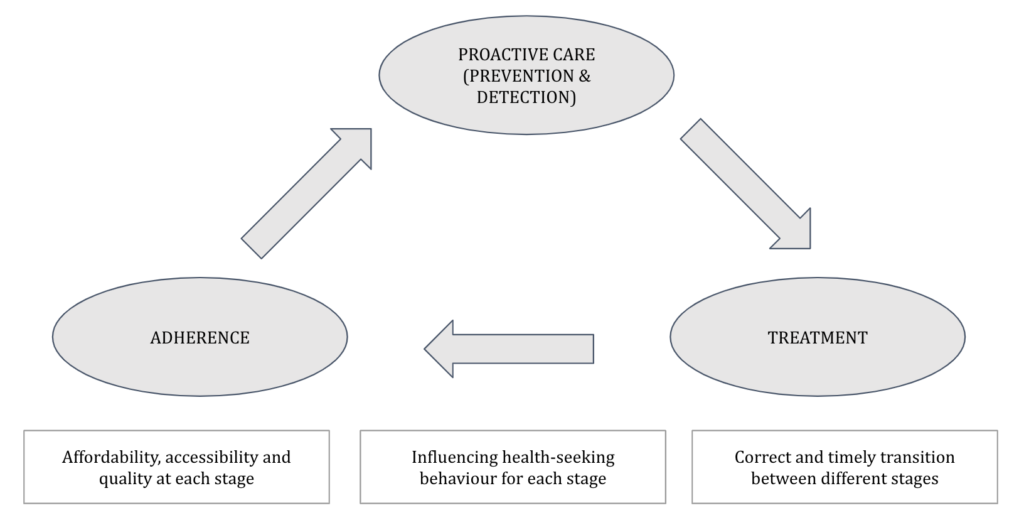

The ground reality in India is that the doctor:patient ratio in the country is low and inequitably distributed. Moreover, the digitization of health data is minimal and the availability of care facilities is sporadic. Taken together, these factors contribute to a relatively subpar standard of public health, which in turn affects happiness and productivity. In a country like India in which each percentage point of productivity and growth corresponds to millions of people moving out of poverty, it is doubly important to bring up the standard of public health as quickly as possible.

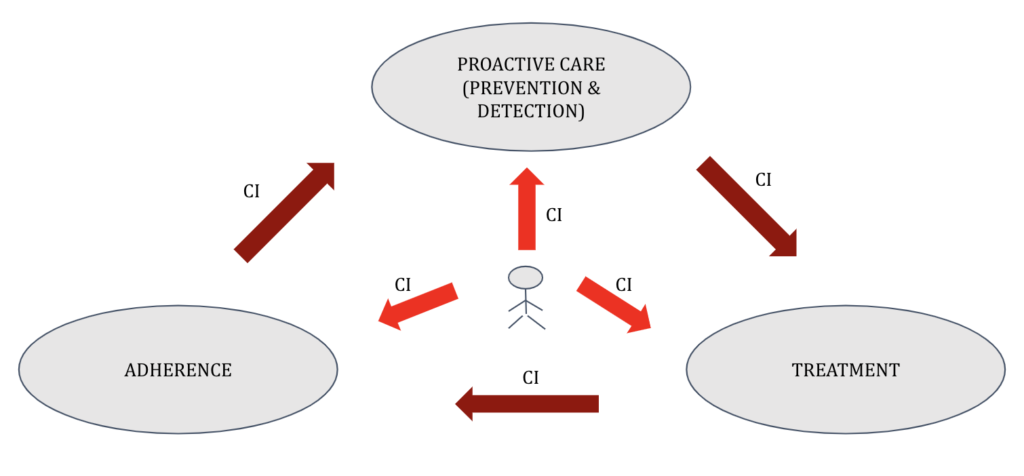

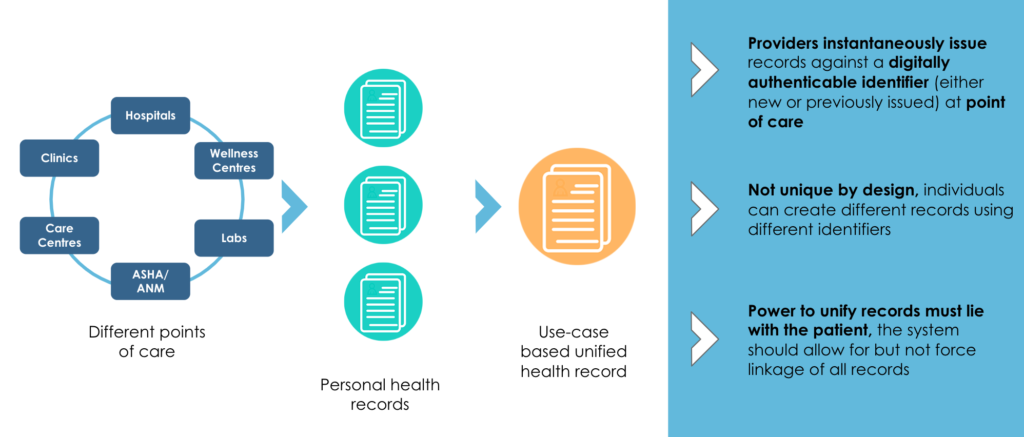

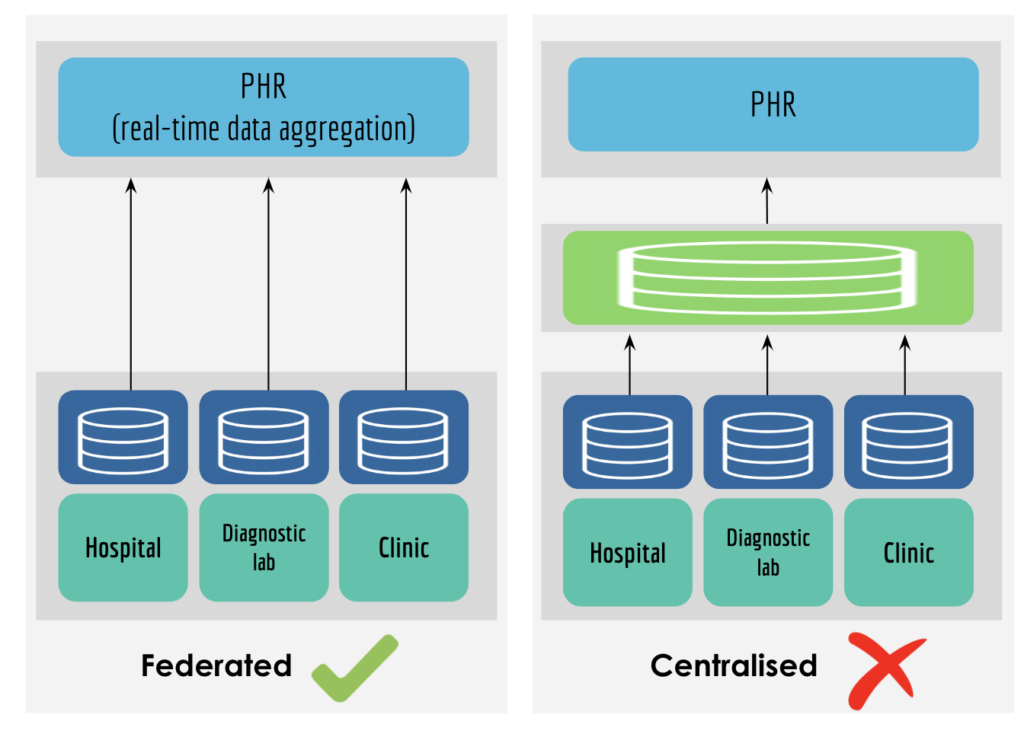

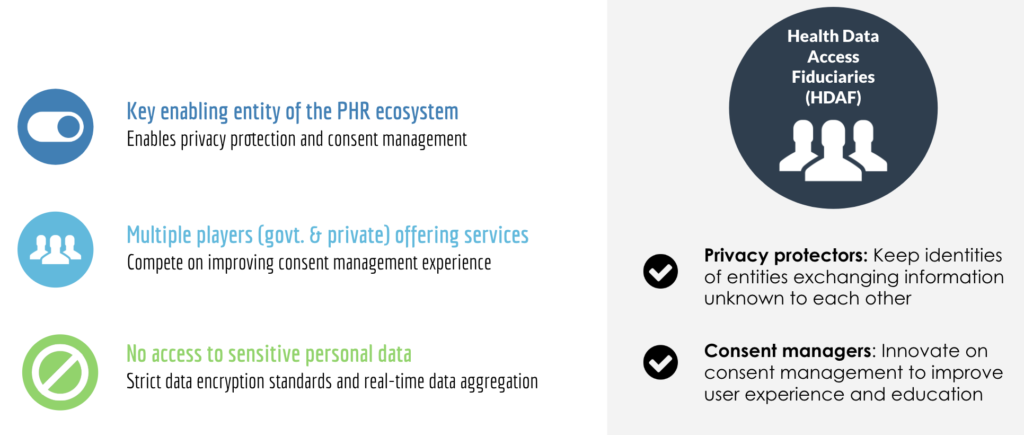

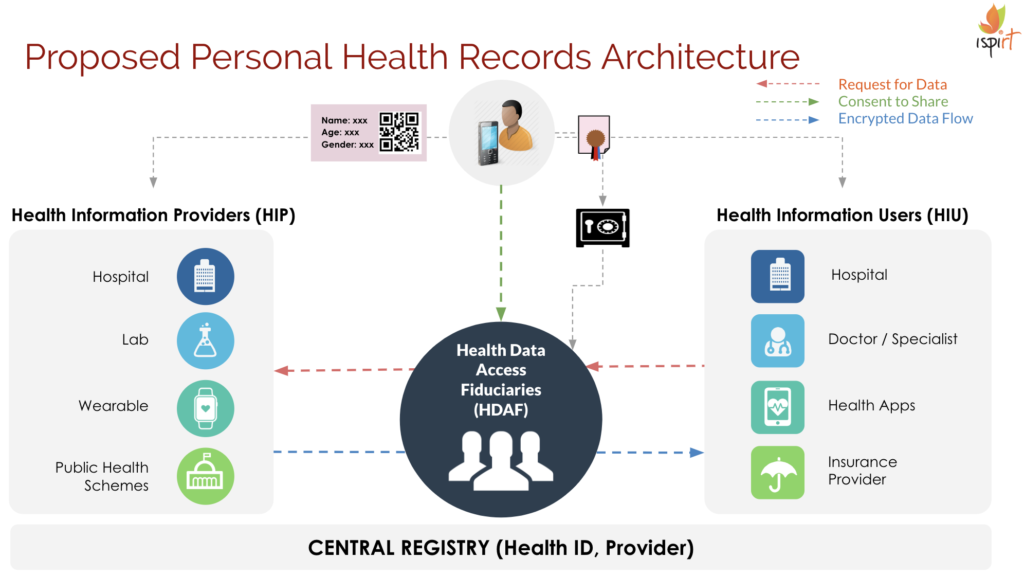

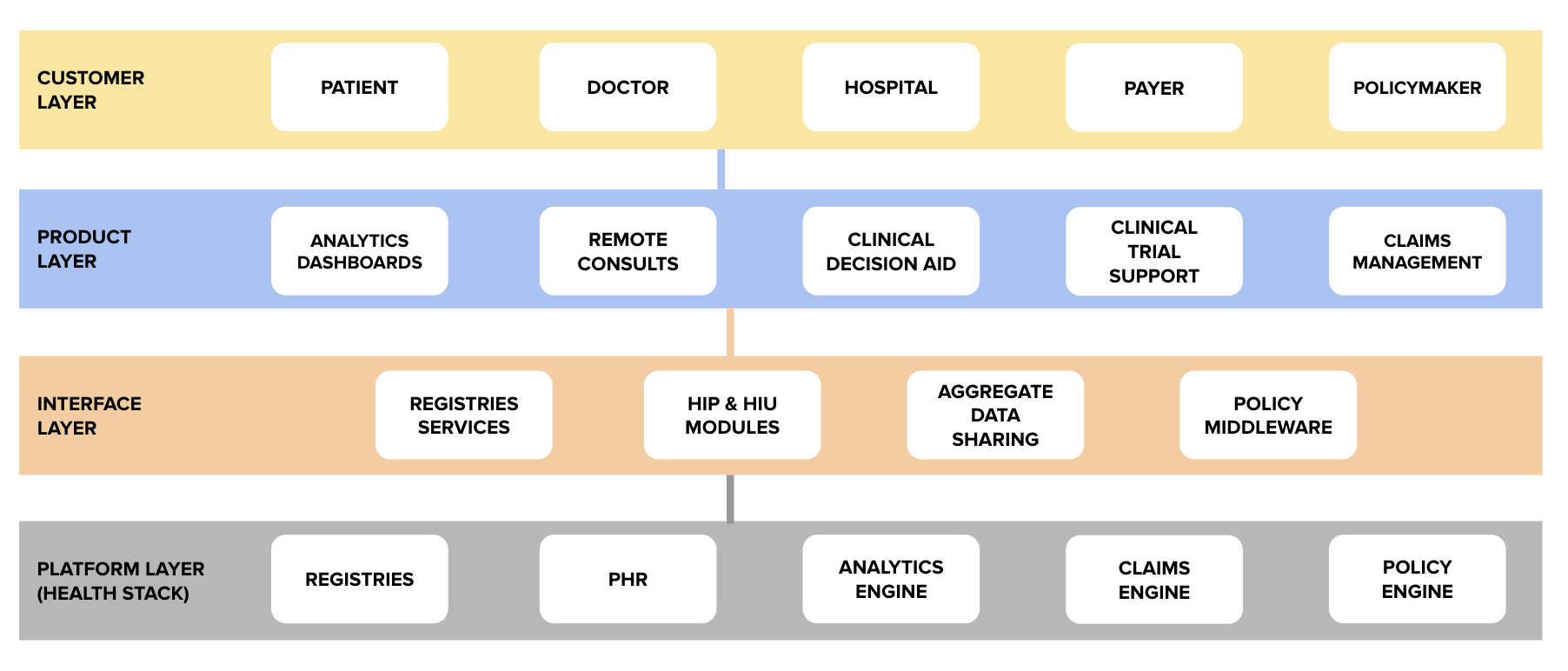

One of the components of the NHS which can do this is the Personal Health Records (PHR) system. This system establishes a standardized interface for storing, managing, and sharing medical data, all with user consent. If users can assert greater control over their own health data, they can derive more utility, convenience, and value. This might take expression through easier access to teleconsultations, or perhaps through a better consumer interface to canvas second opinions about some test reports or medical images. The PHR could also allow for individuals to securely and voluntarily contribute their anonymized healthcare data towards data sets used to map and manage public health trends over time.

The possibilities for the PHR system are many, but it will require a collaboration between the public sector, private sector, and medical community to make the most of this technology. For this reason, we are excited to announce the launch of the Healthathon 2020.

This four-week long virtual conference aims to bring together different stakeholders to work on solutions and products stemming from the PHR system. One key group of stakeholders is the public sector bodies like the NHA and MoHFW, without whose support this initiative can never reach all of the 1.3 billion Indians. The second group is the private sector players such as health tech companies, entrepreneurs, private equity investors, and technology providers – without their creativity, capital, and execution capacity, it will be hard to make any project sustainable or scalable. The last stakeholder group is the medical community of doctors, hospitals, labs, and others; it is clear that without the buy-in and support of this group, no technology intervention can pinpoint or solve the most pressing problems.

Format

The Healthathon 2020 will feature two competitions: the Hackathon and Ideathon. The Ideathon is a 2-week long event aimed at students, medical practitioners, and non-technical parties. During this event, teams will compete to come up with the best business plans and product ideas around the PHR system.

In contrast to the Ideathon, the Hackathon is a 4-week long event aimed at startups, corporates, entrepreneurs, developers, and health tech enthusiasts. As part of the Hackathon, teams of developers will work on building projects on top of the new PHR APIs provided by our sandbox providers.

Participants in both competitions will receive the mentorship, guidance, and resources they need to put out the best possible submissions. Panels of judges will then award prize money to the best teams from each competition.

In addition to the Ideathon and Hackathon, there will also be a slew of masterclasses, panel discussions, and other events. These sessions are intended to generate engagement, awareness, and innovation around the PHR system, and they will all be recorded and open to the public.

We hope that the event will draw in participants from different fields and backgrounds, united in the purpose of leveraging technology to make India healthier, more inclusive, and more efficient.

Hackathon & Ideathon Themes

Some of the themes that teams could choose to work on for the two competitions could include:

End Use Apps:

- Apps that can read healthcare reports and provide some additional context or insight using AI

- Platforms to help create real time monitoring and alerts for doctors using their patient’s wearable device data

- Doctor-facing apps that help unify and analyze patient’s health records across different data sources

- Health lockers for secure and convenient long term storage of health data

- Matching systems that pair patients with the right kind of care provider given a medical report or treatment history

- Anonymised health trends/dashboards for epidemiological studies

- Preventive care applications that promote healthy living by tracking health markers and gamifying healthy living

- Applications that provide and track continued & personalized care plans for chronic disease patients (eg. cancer care)

- New insurance products, possibly featuring fraud prevention and auto-adjudication based on PHR

Consent Management:

- Apps that help the user discover, link, and share access to their medical data

- Building assisted and accessible consent flows for low-literacy or non-smartphone users

- Systems to delegate patient consent in case of emergencies or other extenuating circumstances

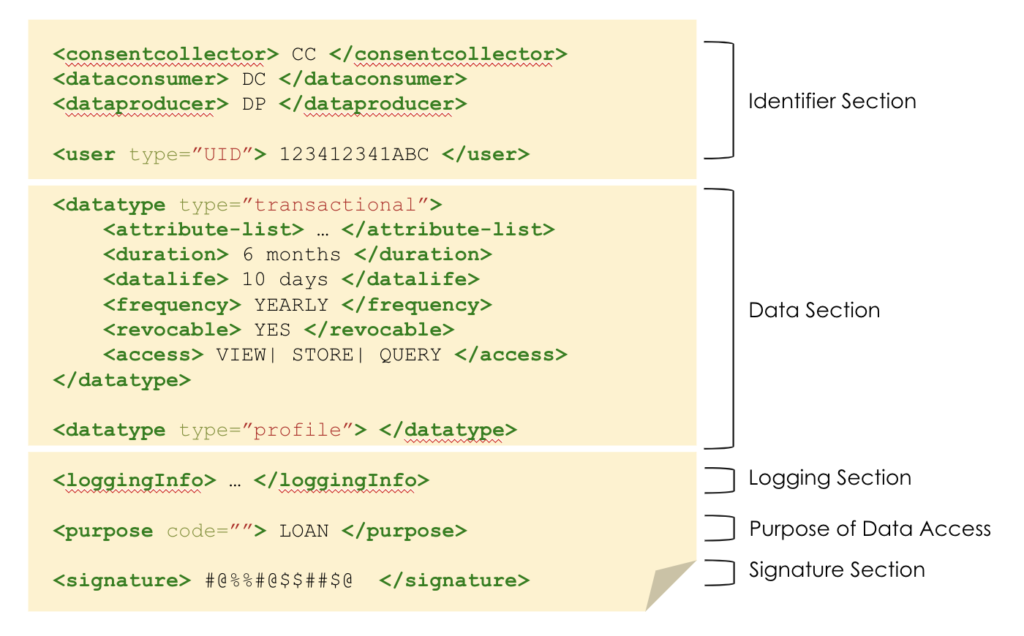

- Consent lifecycle management systems ie. generating, storing, revoking, and safeguarding consent

- Easy and informed consent experiences eg. “scan to share data”, “understand what you are consenting to”

Middleware and Utilities:

- Secure data storage and management facilities

- Tools to help medical institutions adopt and use the PHR system

- AI utilities to decipher and parse medical data

- Developer tools to simplify and abstract the workflows for PHR development

Speakers and Judges

Here is a list of some of the speakers and judges for the event:

- Kiran Mazumdar Shaw, Executive Chairperson, Biocon

- Dr. C. S. Pramesh, Convener, National Cancer Grid

- Sanjeev Srinivasan, CEO, Bharti Axa General Insurance

- Arvind Sivaramakrishnan, Group CIO, Apollo Hospitals

- Nachiket Mor, Commissioner, Lancet Committee on Reimagining Healthcare in India

- Shashank ND, CEO, Practo

- Gaurav Agarwal, CTO, 1mg

- Dr. Ajay Bakshi, CEO, Buddhimed

- Dr. Aditya Daftary, Radiologist, Innovision

- Kiran Anandampillai, Technology Advisor, NHA

- Dharmil Sheth, CEO, PharmEasy

- Pankaj Sahni, CEO, Medanta

- Veneeth Purushotaman, Group CIO, Aster Healthcare

- Yashish Dahiya, CEO, Policybazaar

- Abhimanyu Bhosale, CEO, LiveHealth

- Prabhdeep Singh, CEO, Stanplus

- Rajat Agarwal, Managing Director, Matrix Partners India

- Tarun Davda, Managing Director, Matrix Partners India

Prospective Talks and Masterclasses

- “An overview of the NHS architecture and objectives”

- “A deepdive into the PHR APIs”

- “Medical imaging data: Changing the Status Quo”

- “Using delegated consent to bolster efficacy in emergency care”

- “Technology challenges and opportunities for hospitals and labs”

- “Health Tech in India: successes and areas of improvement”

Sponsors and Partners

Principal Sponsors

- Matrix India Partners

- Swasth Alliance

Knowledge Partners

- CHIME India

- HIMSS India Chapter

Sandbox Providers

- National Health Authority

- LiveHealth

Organization Partner:

- Devfolio

Cash Prizes

Six teams in the hackathon will be eligible to win prizes of Rs. 50,000 each

Five teams in the ideathon will be eligible to win prizes of Rs. 20,000 each.

Dates, Registration, and Outreach

Registration Link (for both events): https://healthathon.devfolio.co

Registrations Close (for both events) : 22nd October, 2020

Opening Ceremony: 24th October, 2020

Ideathon submissions: November 6th, 2020

Hackathon submissions: November 19th, 2020

Closing Ceremony: 22nd November

Outreach: [email protected] (Email subject: “Healthathon”)

Blog Post Image Source: SelectInsureGroup.com