In 1973, the British economist Ernst Schumacher wrote his manifesto “Small is Beautiful”, and changed the world. Schumacher’s prescription — to use technologies that were less resource-intensive, capable of generating employment, and “appropriate” to local circumstances — appealed to a Western audience that worried about feverish consumption by the ‘boomer’ generation. Silicon Valley soon seized the moment, presenting modern-day, personal computing as an alternative to the tyranny of IBM’s Big Machine. Meanwhile, in India too, the government asked citizens to embrace technologies suited to the country’s socio-economic life. Both had ulterior motives: the miniaturisation of computing was inevitable given revolutions in semiconductor technology during the sixties and seventies, and entrepreneurs in Silicon Valley expertly harvested the anti-IBM mood to offer themselves as messiahs. The government in New Delhi too was struggling to mass-produce machines, and starved of funds, so asking Indians to “make do” with appropriate technology was as much a political message as it was a nod to environmentalism.

And thus, India turned its attention to mechanising bullock carts, producing fuel from bio-waste, trapping solar energy for micro-applications, and encouraging the use of hand pumps. These were, in many respects, India’s first “civic”, or socially relevant technologies.

The “appropriate technology” movement in India had two unfortunate consequences. The first has been a celebration of jugaad, or frugal innovation. Over decades, Indian universities, businesses and inventors have pursued low-cost technologies that are clearly not scaleable but valued culturally by peers and social networks. (Sample the press coverage every year of IIT students who build ‘sustainable’ but limited-use technologies, that generate fuel from plastic or trap solar energy for irrigation pumps.) Second, the “small is beautiful” philosophy also coloured our view of “civic technologies” as those that only mobilise the citizenry, out into farms or factory floors. Whether they took the form of a hand pump, solar stove or bullock cart, these technologies did little to augment the productivity of an individual. However, they preserved the larger status quo and did not disrupt social or industrial relations as technological revolutions have historically done.

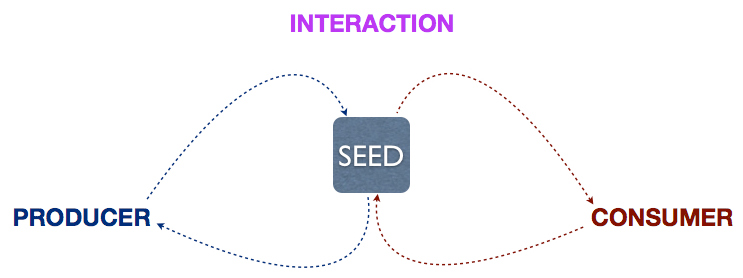

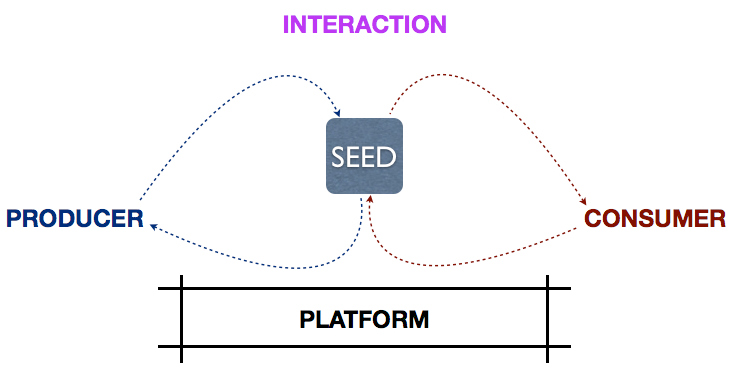

Nevertheless, there has always been a latent demand in India for technologies that don’t just mobilise individuals but also act as “playgrounds”, creating and connecting livelihoods. When management guru Peter Drucker visited post-Emergency India in 1979, Prime Minister Morarji Desai sold him hard on “appropriate technology”. India, Drucker wrote, had switched overnight from championing big steel plants to small bullock carts. Steel created no new jobs outside the factory, and small technologies did not improve livelihoods. Instead, he argued, India ought to look at the automotive industry as an “efficient multiplier” of livelihoods: beyond the manufacturing plant, automobiles would create new sectors altogether in road building and maintenance, traffic control, dealerships, service stations and repair. Drucker also pointed to the transistor as another such technology. Above all, transistors and automobiles connected Indians to one another through information and travel. Drucker noted during his visit that the motor scooter and radio transistor were in great demand in even far-flung corners, a claim that is borne by statistics. These, then were the civic technologies that mattered, ones that created playgrounds in which many could forge their livelihoods.

The lionisation of jugaad is an attitudinal problem, and may not change immediately. But the task of creating a new generation of civic technologies that act as playgrounds can be addressed more readily. In fact, it is precisely during crises such as the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic that India acutely requires such platforms.

Consider the post-lockdown task of economic reconstruction in India, which requires targeted policy interventions. Currently, the Indian government is blinkered to address only two categories of actors who need economic assistance: large corporations with their bottom lines at risk, and at the micro-level, individuals whose stand to lose livelihoods. India’s banks will bail out Big Business, while government agencies will train their digital public goods — Aadhaar, UPI, eKYC etc — to offer financial assistance to individuals. This formulaic approach misses out the vast category of SMEs who employ millions, account for nearly 40% of India’s exports, pull in informal businesses into the supply chain and provide critical products to the big industries.

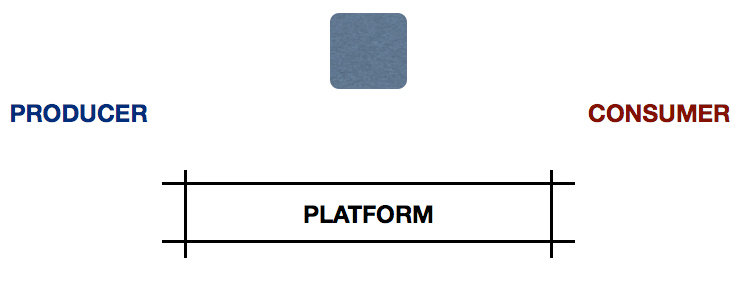

To be sure, the data to identify SMEs (Income Tax Returns/ GSTN/ PAN) exists, as do the digital infrastructure to effect payments and micro-loans. The funds would come not only from government coffers but also through philanthropic efforts that have gained steam in the wake of the pandemic. However, the “playground” needs to be created — a single digital platform that can provide loans, grants or subsidies to SMEs based on specific needs, whether for salaries, utilities or other loan payments. A front-end application would provide any government official information about schemes applied for, and funds disbursed to a given SME.

Civic technologies in India have long been understood to mean small-scale technologies. This is a legacy of history and politics, which policymakers have to reckon with. The civic value of technology does not lie in the extent to which it is localised, but its ability to reach the most vulnerable sections of a stratified society like India’s. The Indian government, no matter how expansive its administrative machinery is, cannot do this on its own. It has to create “playgrounds” — involving banks, cooperative societies, regulators, software developers, startups, data fiduciaries and underwriting modellers — if it intends to make digital technologies meaningful and socially relevant.

Please Note: A version of this was first published on Business Standard on 17 April 2020

About the author: Arun Mohan Sukumar is a PhD candidate at the Fletcher School, Tufts University, and a volunteer with the non-profit think-tank, iSPIRT. He is currently based in San Francisco. His book, Midnight’s Machines: A Political History of Technology in India, was published by Penguin Random House in 2019

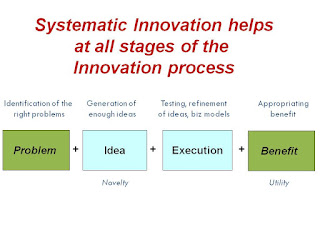

ian companies need to embrace systematic innovation so as to capitalize on their innate abilities of intuition and market sensing. Vinay Dabholkar and I hope that 2013 will be the year for systematic innovation in India. May systematic innovation go viral! Our own contribution towards this will be released soon – watch this space for more details!

ian companies need to embrace systematic innovation so as to capitalize on their innate abilities of intuition and market sensing. Vinay Dabholkar and I hope that 2013 will be the year for systematic innovation in India. May systematic innovation go viral! Our own contribution towards this will be released soon – watch this space for more details!