The Industrial Revolution was possible because organizations could be built and managed effectively. Today too, problem #1 in business is creating the organization in the right way.

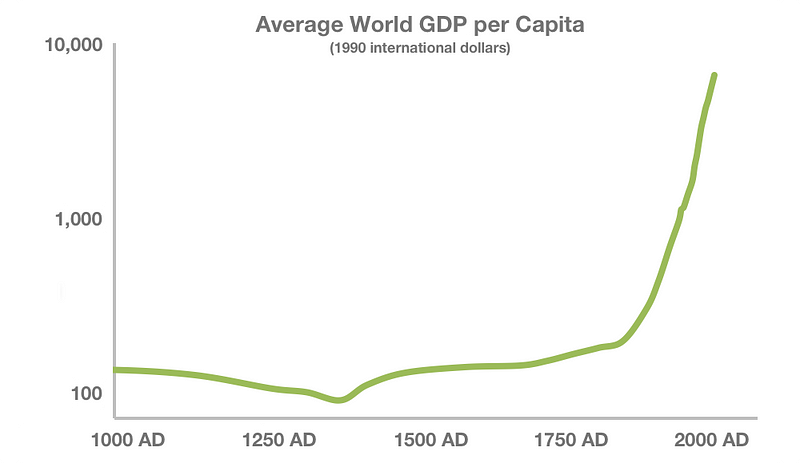

The first time I saw this chart below, a light bulb went off in my head.

It shows the world’s average GDP per capita over the past thousand years. It is basically represents an average human’s economic productivity over time. Note: this is on a log scale.

I mainly want to talk about the last couple of hundred years in this chart, but let’s get a couple of things out of the way upfront. Firstly, the GDP estimates go back a million years, but most of human history is rather uneventful from an economic perspective. Secondly, the dip around 1300 AD is due to the “Black Death” plague that killed nearly a third of the world’s population, most devastatingly in Europe.

After the plague, productivity recovered with the population, and started improving as we kept getting a little better at what we did. But what made the line shoot up so drastically in the 19th century?

The Industrial Revolution happened.

Firstly, technology.

There were newer, more sophisticated machines that made large scale manufacturing possible, and there was power available to run these machines.

The textile industry is everyone’s favorite example. Historically, production of cloth used to be largely a domestic enterprise and sometimes a cottage industry. Farmers’ wives would spin the cotton at home, and the men would then weave it into cloth. It would take four to eight spinners to supply one handloom weaver. Enter the Industrial Revolution: at the time the textile industry was inventing the Flying Shuttle and the Power Loom, the steam engine was also being invented. And very quickly, the two came together to enable large factories where steam-powered machines would do the work of hundreds of people.

Secondly, people formed organizations.

The most important part (in my mind) of the Industrial Revolution was the rise of the business organization and of management as a function.

While the initial spurts of technological advancement led to the creation of many businesses, they were still run by one or a few owners or partners trying to do everything, and that could not scale. You could draw an analogy with startups today, but it wouldn’t be accurate as we do have access to management tools. Back then, it just didn’t exist. The railroad companies spearheaded the science and practice of management, being one of the largest organizations and requiring large numbers of people across different aspects of the entire operation to act as one unit. They realized they could organize into departments and appoint managers who planned tasks and supervised the workers that carried out those tasks.

Organizations of an unprecedented size and scale could exist because of this, kicking off many self-fueling virtuous cycles, and not just enabling co-ordination across a large enterprise but also dramatically improving processes and workforce utilization. This is what made the right side of the chart possible.

While it seems like a blip in history, this took time: nearly two hundred years. It completely elevated what we as a species are capable of, but also came at a great societal cost (large scale unemployment and severe exploitation of those that were employed).

And it hasn’t ended: that line is only going up (and perhaps with different kinds of costs).

Now, based on all this, I’m going to posit:

Now, based on all this, I’m going to posit:

The key to all progress lies in creating scalable organizations.

Misallocating Entrepreneurship

There is an interesting example that elucidates this point. This article — India is a much more Entrepreneurial Society than the United States (and that’s a problem) — talks about the problems when a society cannot scale its organizations:

India is a much more entrepreneurial society than the United States. That may seem surprising since India is poor and we typically associate entrepreneurship with being rich but it’s clearly true. Only ~15% of Indians work for a firm compared to approximately 90% of US workers.

It digs into why it can be a problem.

Entrepreneurship in India isn’t a choice, it’s a requirement. Indian entrepreneurship is a consequence of India’s failed economy. The problem with developing countries is not that they lack entrepreneurs but that entrepreneurs cannot grow their firms large enough to become major employers.

Entrepreneurship, like other factors of production, can be misallocated. India has great entrepreneurs but their hard work, creativity, and risk taking is being wasted building tiny, stunted firms.

Entrepreneurship, like other factors of production, can be misallocated.

But our culture is becoming more individualistic, in all aspects of society. In business, everyone wants to be the entrepreneur, and is looking for “non-entrepreneurs” to recruit to their cause. And it has never been easier to start a company — limited liability and easy access to capital, distribution and technology have made sure of that.

Perhaps the optimal size of the firm will change in response to these forces, but I don’t see evidence of that yet — quite the opposite, if anything. Perhaps this chart above will sober up for a bit, or perhaps technology (general AI?) will render people irrelevant in the scheme of things. Until then, building high-functioning, scalable organizations that fit into the cultural mood will have to be the foremost problem company-builders need to solve.

(Huge thanks to Michael Dearing for showing me this chart for the first time, and opening up the first principles of management for me. I highly recommend his General Management course.)