Building a software product is more difficult than doing projects or providing services. With projects, software is developed to meet the exact specifications of the client. Work begins only when the contract is signed.

The project scope can be defined accurately in consultation with the customer, and deployment happens in a controlled environment at client site, with known hardware and software. Support requirements are minimal.

Changes to specifications, or defects during development or after deployment, usually have limited financial impact. In T&M contracts, the vendor is paid regularly, based on efforts put in. Hence, changes and delays may in fact, bring in more revenue. Fixed price bids usually account for contingencies like delays. If specifications are changed, the vendor can ask to re-negotiate the price. Quality issues may cause loss of credibility, or at worse, project termination and denial of future contracts.

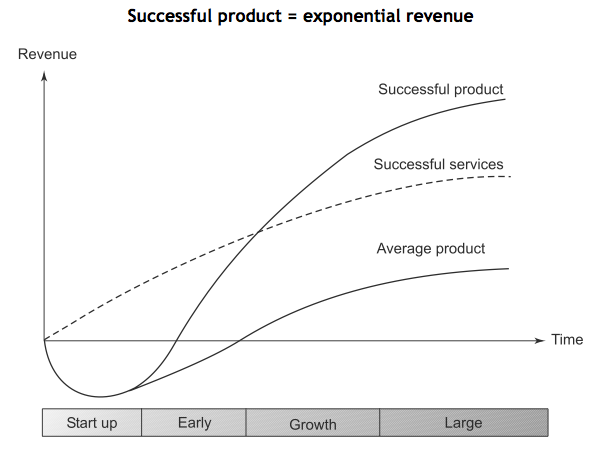

A product, in contrast, will be shipped to thousands, or even millions of users. Specifications are based on the seller’s understanding of customer needs. Therefore, a deep knowledge of market and domain is required. Clients are not guaranteed, and marketing and sales functions are critical. Selling cycles are longer and more cumbersome.

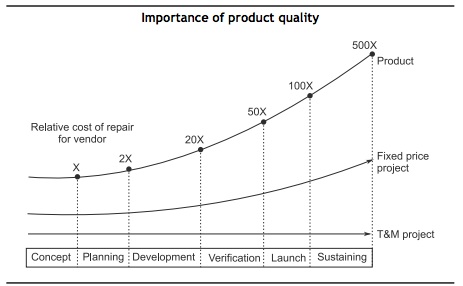

Quality has to be outstanding, since the product will be used by a variety of users, and on a plethora of platforms and configurations, and not all of it can be anticipated in advance. As the diagram below shows, the cost of fixing a defect increases exponentially depending on when it is detected.

A post-release defect creates negative publicity and costs lot of money. A patch to fix the problem has to be developed and distributed quickly to the users. Even Microsoft has faced this problem repeatedly when hackers have exploited vulnerabilities in its operating systems. In another instance, a US-based personal finance company inadvertently exposed the private account details of several hundred individuals to other users. Such snafus can expose a product company

to expensive lawsuits.

A product business requires highly structured engineering and organizational discipline. Formal reviews are necessary at every stage (architecture, design, coding) to catch deviations from the requirements. Rigorous testing and quality assurance (test/QA) processes should be followed to detect defects before product release. Test labs must replicate the myriad deployment environments that users may have. This can become complicated for multi-platform products that support a variety of operating systems (Windows, Unix, Linux) and databases.

The installation procedure must be highly automated and work fl awlessly in all possible system configurations. New versions, patches, and future upgrades must install without any disruption to existing software and data at user sites. A strong support organization (on phone, email or onsite) has to be built.

Unlike projects, there is no end date for product engineering. They must continue innovating and releasing new versions with more functionality and advanced features, to stay ahead of competition. Product organizations often have a signifi cant revenue component derived from services such as consulting, customization, integration and solutions. Unlike a pure services business, these are used to underpin and drive their product sales.

The ecosystem for products is more complex, consisting of engineering teams, product management, marketing, sales, consulting, professional services, distributors, system integrators, resellers and investors.

Reprinted from From Entrepreneurs to Leaders by permission of Tata McGraw-Hill Education Private Limited.