It has been a while since our last blog on this topic. After a break of two weeks, we recently completed the fifth Open House Discussion on the National Health Stack (NHS).

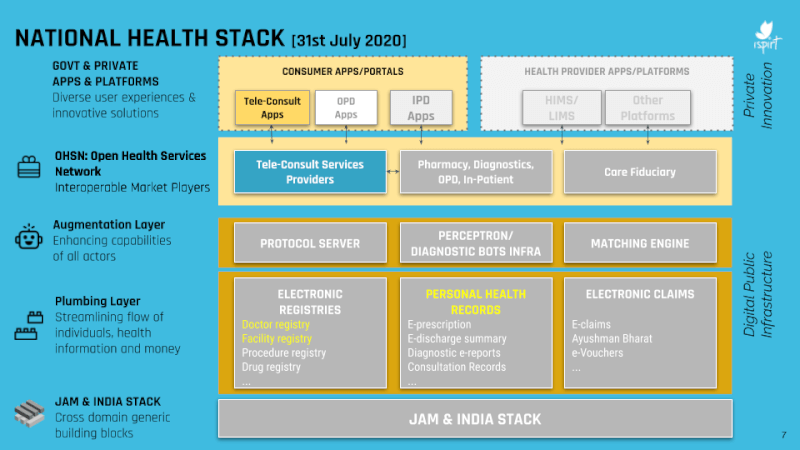

In this session, held from 11:30 am-12 pm on 31st July 2020, our volunteers Sharad Sharma, Siddharth Shetty, and Dr Pramod Varma talked about the Open Health Services Network (OHSN – pronounced ‘ocean’).

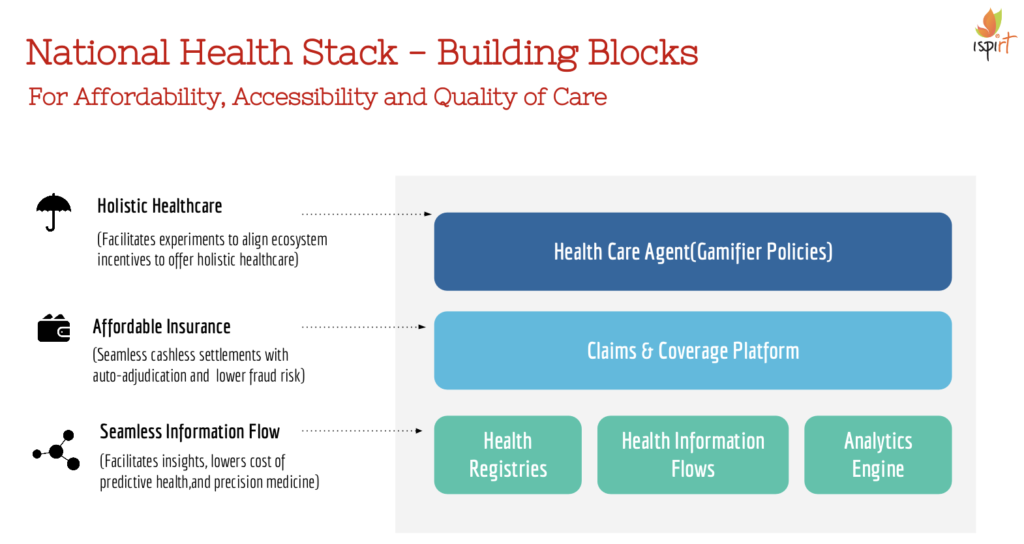

As a refresher, the OHSN is the interface which governs the relationship between various market players in the healthcare ecosystem such as tele consult providers, pharmacies, or diagnostic centres on one side, and government or private apps and platforms on the other side.

It is important for these relationships to be properly streamlined and mapped out for two reasons:

- To establish baseline standards of care

- And to provide auditable and transparent processes governing the transfer of data and payments

If these two objectives are met, the healthcare ecosystem as a whole can be made more accessible, secure, and efficient for both users and service providers.

This session focused upon the specific relationship between teleconsultation service providers and end-user apps (EUAs) offering teleconsultation services.

From the perspective of OSHN, tele consultations involve three players:

- the EUA (an end-user app selected by the user)

- an OHSN gateway (a matching agent of sorts)

- a telehealth service provider (‘provider’)

The process follows these steps:

- The user signs up on an EUA

- The user searches for doctors/consultations

- The OHSN gateway forwards this customer intent to the network of providers

- Providers reply with tele consultation offerings

- The user selects the preferred offering on the EUA interface

- The user then confirms the session with the provider

- The user conducts a pre-consult with the provider through their EUA

- The consultation takes place over a medium offered by the EUA (could be SMS, chat, video, audio, VoIP)

- The consultation then gets completed and the doctor sends over their consultation notes and prescription from the provider app to the EUA.

All these steps are standardized so that any EUA can talk to any provider app to facilitate this flow. The API specifications for this are laid out at https://bit.ly/2X6skVV (Version 0.5). These APIs were developed in association with beckn.org, an open protocol for distributed commerce.

To learn more about this flow and to hear Sharad, Sid, and Pramod talk about the OHSN principles and APIs, you can visit this link: https://youtu.be/kI7aQw3BUTc

In order to ask some questions which can be answered during the next Open House Session, you can visit https://bit.ly/NHS-QAForm

The next seventh Open House Discussion about the National Health Stack takes place tomorrow, Saturday, August 1st, at 11:30 am. The topic for discussion is the PHR (Personal Health Records) economic model. Interested parties can watched the recording here: https://youtu.be/Y5MIEB1TPw4

The following Open House Discussion will focus upon the OHSN technology architecture, and will take place on Saturday, 15th August at 11:30 am. The link for this session is the same as above – https://bit.ly/NHS-OHD

We hope this summary was useful and we look forward to engaging with you during the next Open House Discussion!

PS. Any parties interested in implementing or contributing to these APIs can reach out to [email protected] with the subject line “Interested in technical contributions for NHS”